mardi 30 novembre 2010

La Proie du Vent 1926

lundi 29 novembre 2010

Le Lion des Mogols 1924

jeudi 25 novembre 2010

Förseglade Läppar 1927

dimanche 21 novembre 2010

Feu Mathias Pascal 1924

Un film de Marcel L'Herbier avec Ivan Mosjoukine, Lois Moran, Marcelle Pradot, Michel Simon et Pauline Carton

Un film de Marcel L'Herbier avec Ivan Mosjoukine, Lois Moran, Marcelle Pradot, Michel Simon et Pauline Cartonjeudi 18 novembre 2010

Le Brasier Ardent 1923

Un film d'Ivan Mosjoukine avec Ivan Mosjoukine, Nathalie Lissenko et Nicolas Koline

Un film d'Ivan Mosjoukine avec Ivan Mosjoukine, Nathalie Lissenko et Nicolas Kolinemercredi 17 novembre 2010

Within Our Gates 1920

Sylvia Landry (E. Preer), une jeune institutrice afro-américaine, part pour les états du sud. Elle est embauchée dans une école tenue par un pasteur qui veut éduquer les afro-américains illétrés...

mardi 16 novembre 2010

Suzanne Grandais (1893-1920)

Henri Fescourt raconte que Mary Pickford l’ayant vu dans La Dentellière (1912, L. Perret) où elle joue une jeune hollandaise décida d’interpréter à son tour un rôle semblable. L’anecdote semble véridique car Mary Pickford joua effectivement dans Hulda from Holland (1916, J. O’Brien).

Henri Fescourt raconte que Mary Pickford l’ayant vu dans La Dentellière (1912, L. Perret) où elle joue une jeune hollandaise décida d’interpréter à son tour un rôle semblable. L’anecdote semble véridique car Mary Pickford joua effectivement dans Hulda from Holland (1916, J. O’Brien).Elle est née Suzanne Gueudret en 1893 à Paris. Elle est découverte au Moulin-Rouge, où elle est danseuse, par un metteur en scène de cinéma Robert Saidreau. Ses premières bandes passent inaperçues. Mais, tout change lorsqu’elle est repérée au théâtre par Léonce Perret. Il est alors l’un des plus grands metteurs de la Gaumont. Elle devient son interprète préférée dans la comédie et le drame. L’autre grand nom de Gaumont, Louis Feuillade va aussi l’utiliser dans de nombreux courts-métrages. Voici comment Henri Fescourt la décrit lorsqu’il arrive pour la première fois au studio Gaumont : « …une scène illuminée par la présence d’une jeune interprète toute blonde, toute rose, toute légère et ensoleillée. Cette apparition miraculeuse n’était autre que celle de Suzanne Grandais, qui devint la deuxième vedette française internationale, après Max Linder. »

En ce début des années 10, les stars féminines de l’écran sont encore rares. Le cinéma n’utilise pas encore le gros plan et le nom des acteurs est rarement mentionné au générique. Avec de tels handicaps, on ne peut être qu’admiratif face à la réussite plusieurs dames de l’écran en 1910. Il y la superbe danoise Asta Nielsen avec sa taille élancée, sa sensualité et son charisme. En France, Mistinguett est à l’affiche des comédies Pathé. Elle aussi a une personnalité suffisamment forte pour s’imposer à l’écran. Ses rôles de femme forte et indépendante – finalement assez proches de ceux de Nielsen – lui permette de sortir des clichés habituels de la femme soumise de l’époque. Mais, Suzanne Grandais est un personnage encore différent. Elle offre encore une fraîcheur innocente qui la distingue des femmes plus mûres jouées par ses deux rivales. Son visage mutin conserve une beauté qui ne déparerait pas un film contemporain. Bien qu’elle soit enveloppée d’un corset, on devine une silhouette fine et mince aux courbes voluptueuse. Elle n’a que 17 ans lorsqu’elle tourne son premier film avec Léonce Perret. L’image de la jeune fille ne se précisera à l’écran que plus tard avec Lillian Gish et Mary Pickford. Grandais offre alors une image nouvelle de la femme.

En ce début des années 10, les stars féminines de l’écran sont encore rares. Le cinéma n’utilise pas encore le gros plan et le nom des acteurs est rarement mentionné au générique. Avec de tels handicaps, on ne peut être qu’admiratif face à la réussite plusieurs dames de l’écran en 1910. Il y la superbe danoise Asta Nielsen avec sa taille élancée, sa sensualité et son charisme. En France, Mistinguett est à l’affiche des comédies Pathé. Elle aussi a une personnalité suffisamment forte pour s’imposer à l’écran. Ses rôles de femme forte et indépendante – finalement assez proches de ceux de Nielsen – lui permette de sortir des clichés habituels de la femme soumise de l’époque. Mais, Suzanne Grandais est un personnage encore différent. Elle offre encore une fraîcheur innocente qui la distingue des femmes plus mûres jouées par ses deux rivales. Son visage mutin conserve une beauté qui ne déparerait pas un film contemporain. Bien qu’elle soit enveloppée d’un corset, on devine une silhouette fine et mince aux courbes voluptueuse. Elle n’a que 17 ans lorsqu’elle tourne son premier film avec Léonce Perret. L’image de la jeune fille ne se précisera à l’écran que plus tard avec Lillian Gish et Mary Pickford. Grandais offre alors une image nouvelle de la femme. avec Léonce Perret dans les comédies Léonce où il joue le rôle principal. Elle est son épouse et se chamaille régulièrement avec lui pour des broutilles. Elle n’est pas foncièrement comique. Elle se contente de servir de caisse de résonance à Léonce. Et c’est ce contraste entre elle, fraîche et volontaire face à lui, bonasse et légèrement coquin qui fonctionne à merveille.

avec Léonce Perret dans les comédies Léonce où il joue le rôle principal. Elle est son épouse et se chamaille régulièrement avec lui pour des broutilles. Elle n’est pas foncièrement comique. Elle se contente de servir de caisse de résonance à Léonce. Et c’est ce contraste entre elle, fraîche et volontaire face à lui, bonasse et légèrement coquin qui fonctionne à merveille. Dans le tragique, elle est aussi remarquable. J’admire énormément son interprétation dans Le Cœur et l’Argent (1912, L. Feuillade ou L. Perret ?). Elle y est la fille d’une aubergiste poussée à faire un mariage d’argent par sa mère. Elle obéit à ce commandement et abandonne son petit ami au profit d’un homme riche et plus âgé. Devenue veuve, espérant pouvoir retrouver son ancien ami, elle découvre qu’il ne l’aime plus. Désespérée, elle se suicide en se jetant dans la rivière. Son corps part au fil de l’eau telle Ophélie. Le film a une poésie toute particulière due à la beauté de la cinématographie de Georges Specht qui évoque Manet. Mais, Suzanne réussit à nous faire vivre son personnage avec un jeu de physionomie très subtile, bien qu’étant filmée toujours en plan large. De même dans Le Mystère des Roches de Kador (1912, L. Perret) où elle devient folle à cause du meurtre de son amant par son cousin. Elle retrouve ses sens face à un film qui recrée le meurtre. De même, on lit sur son visage la soudaine détresse du souvenir qui revient. Perret en fait aussi une héroine tragique qui se suicide sur la côte rocheuse de Biarritz suite au décès de son amant dans La Rançon du Bonheur (1912) où elle rappelle les grandes divas italiennes, mais sans leurs excès.

Dans le tragique, elle est aussi remarquable. J’admire énormément son interprétation dans Le Cœur et l’Argent (1912, L. Feuillade ou L. Perret ?). Elle y est la fille d’une aubergiste poussée à faire un mariage d’argent par sa mère. Elle obéit à ce commandement et abandonne son petit ami au profit d’un homme riche et plus âgé. Devenue veuve, espérant pouvoir retrouver son ancien ami, elle découvre qu’il ne l’aime plus. Désespérée, elle se suicide en se jetant dans la rivière. Son corps part au fil de l’eau telle Ophélie. Le film a une poésie toute particulière due à la beauté de la cinématographie de Georges Specht qui évoque Manet. Mais, Suzanne réussit à nous faire vivre son personnage avec un jeu de physionomie très subtile, bien qu’étant filmée toujours en plan large. De même dans Le Mystère des Roches de Kador (1912, L. Perret) où elle devient folle à cause du meurtre de son amant par son cousin. Elle retrouve ses sens face à un film qui recrée le meurtre. De même, on lit sur son visage la soudaine détresse du souvenir qui revient. Perret en fait aussi une héroine tragique qui se suicide sur la côte rocheuse de Biarritz suite au décès de son amant dans La Rançon du Bonheur (1912) où elle rappelle les grandes divas italiennes, mais sans leurs excès. Suzanne avait tout pour devenir une icône du cinéma. Sa mort tragique en 1920, à l’âge de 27 ans, dans un accident de voiture la fige à tout jamais dans l’image de la jeune fille parisienne des films Gaumont. Henri Fescourt parle de son ‘sex-appeal fluide et pénétrant’. Elle conserve sans aucun doute un attrait pour le spectateur contemporain et mérite d’être redécouverte.

Suzanne avait tout pour devenir une icône du cinéma. Sa mort tragique en 1920, à l’âge de 27 ans, dans un accident de voiture la fige à tout jamais dans l’image de la jeune fille parisienne des films Gaumont. Henri Fescourt parle de son ‘sex-appeal fluide et pénétrant’. Elle conserve sans aucun doute un attrait pour le spectateur contemporain et mérite d’être redécouverte.L'Empire du Diamant 1920-22

lundi 15 novembre 2010

Kevin Brownlow Interview (Part V)

Part 5

Part 5 Hardly anybody that I interviewed didn’t rave about Griffith and didn’t acknowledge The Birth of a Nation as the greatest thing they’d seen. What is extraordinary to me now is that we didn’t discuss the politics. Now I’d seen the picture at a 13 year old with a school friend at the Everyman Theatre in Hampstead when they were running the sound version. And the sound version is catastrophic because it’s speeded up. Griffith having shot it at 16 fps, it’s now shown at 24 fps. It looks absolutely ridiculous. It’s also terrible quality and we both came out saying: “What a load of rubbish!” But we didn’t respond to the fact that the Ku Klux Klan were the heroes and the blacks were the villains. And when I spoke to people who remembered the picture, the first time round, they all regarded it as cowboys and Indians, besides being tremendously proud of the film as a member of the industry who produced it. And raving about Griffith. I don’t remember anybody pointing out the all to obvious fact that it was wildly racist! So that is curious. When I saw a Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films, they asked the great film makers what films they regarded as memorable, Carl Dreyer –of all people!- chose The Birth of a Nation as number one. So despite the riots they talk about and the protests at the time, it obviously had a very different reaction on people. And I think that the appalling thing to admit is that it was generally accepted that blacks were not exactly sub-human but getting that way. And these wonderful men in white were indeed worthy of being the heroes. The ironic thing is Griffith and Dixon who wrote The Birth of a Nation, were opposed to the resurgence of the Klan which The Birth of a Nation did so much to help. However, if you take part one, it is the most moving pacifist film. It’s only in part two that it gets really vicious…but it’s so exciting…to think that it’s a film made in 1915. If you see it with an orchestra, it’s absolutely pile driving, the ride of the Valkyries being played for the ride of the Klan. But you don’t show it in public, it’s still the most controversial film ever made. I tell you one thing, Madam Sul-Te-Wan who was a black actress in The Birth of a Nation was asked about Griffith and she said: “If my father and Mr Griffith were drowning in the river, I’d step on my father to rescue Mr Griffith.”

Hardly anybody that I interviewed didn’t rave about Griffith and didn’t acknowledge The Birth of a Nation as the greatest thing they’d seen. What is extraordinary to me now is that we didn’t discuss the politics. Now I’d seen the picture at a 13 year old with a school friend at the Everyman Theatre in Hampstead when they were running the sound version. And the sound version is catastrophic because it’s speeded up. Griffith having shot it at 16 fps, it’s now shown at 24 fps. It looks absolutely ridiculous. It’s also terrible quality and we both came out saying: “What a load of rubbish!” But we didn’t respond to the fact that the Ku Klux Klan were the heroes and the blacks were the villains. And when I spoke to people who remembered the picture, the first time round, they all regarded it as cowboys and Indians, besides being tremendously proud of the film as a member of the industry who produced it. And raving about Griffith. I don’t remember anybody pointing out the all to obvious fact that it was wildly racist! So that is curious. When I saw a Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films, they asked the great film makers what films they regarded as memorable, Carl Dreyer –of all people!- chose The Birth of a Nation as number one. So despite the riots they talk about and the protests at the time, it obviously had a very different reaction on people. And I think that the appalling thing to admit is that it was generally accepted that blacks were not exactly sub-human but getting that way. And these wonderful men in white were indeed worthy of being the heroes. The ironic thing is Griffith and Dixon who wrote The Birth of a Nation, were opposed to the resurgence of the Klan which The Birth of a Nation did so much to help. However, if you take part one, it is the most moving pacifist film. It’s only in part two that it gets really vicious…but it’s so exciting…to think that it’s a film made in 1915. If you see it with an orchestra, it’s absolutely pile driving, the ride of the Valkyries being played for the ride of the Klan. But you don’t show it in public, it’s still the most controversial film ever made. I tell you one thing, Madam Sul-Te-Wan who was a black actress in The Birth of a Nation was asked about Griffith and she said: “If my father and Mr Griffith were drowning in the river, I’d step on my father to rescue Mr Griffith.”The Birth of a Nation is nowadays a very controversial film. Its blatant racism makes it a very disturbing feature. In the documentary, you managed to give a very balanced view of the film and its film-maker. How did you start to tackle this difficult subject?

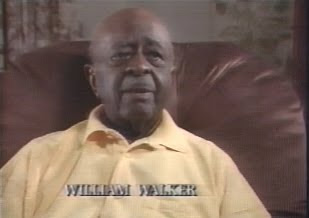

Well, a miracle happened! We were making a film about Harold Lloyd and went to see one of his kid actors, Peggy Cartwright who played in one of his two-reelers and she was in her late 70s, I suppose. And the last person you would think would introduce a husband who was black. She was married to an actor called William Walker and he had been at the first showing of The Birth of a Nation and he gave us an account of what it was like to see that film as a black man and it was terribly moving. And what we couldn’t include was his description of how after the show he stood on the street and watched the Klan march. But that was the absolute miracle of good fortune that we found somebody who was so eloquent about the picture. And I thought that was enough. But PBS in America, decided we had to have two black academics as well. So for the American version, they got John Hope Franklin and without checking they got Tom Cripps who has written a lot about black films, only he’s white! (laugh) They were very dismayed when he arrived for the filming and discovered they got the wrong man. (laugh) Anyway, I don’t think what either of them say changes the balance of what we had with William Walker.

Well, a miracle happened! We were making a film about Harold Lloyd and went to see one of his kid actors, Peggy Cartwright who played in one of his two-reelers and she was in her late 70s, I suppose. And the last person you would think would introduce a husband who was black. She was married to an actor called William Walker and he had been at the first showing of The Birth of a Nation and he gave us an account of what it was like to see that film as a black man and it was terribly moving. And what we couldn’t include was his description of how after the show he stood on the street and watched the Klan march. But that was the absolute miracle of good fortune that we found somebody who was so eloquent about the picture. And I thought that was enough. But PBS in America, decided we had to have two black academics as well. So for the American version, they got John Hope Franklin and without checking they got Tom Cripps who has written a lot about black films, only he’s white! (laugh) They were very dismayed when he arrived for the filming and discovered they got the wrong man. (laugh) Anyway, I don’t think what either of them say changes the balance of what we had with William Walker.But I do think that The Birth of a Nation ought to be seen and not censored. It’s not the American way to censor pictures. I think it’s even against the Constitution. They tried hard enough over the years. It’s always been disastrous. If you hide something away, and then build up the reputation, I think it does more damage than showing it and letting people make up their own mind. But in that case, for that film, you really have to show it looking at its best for the artistic impact was so enormous and you need to know why. Nobody remembers now that Fox put out a picture in the same year called The Nigger (1915, Edgar Lewis). But the film is lost and nobody bothers about it. But that was just as controversial in its way, in its small way, as The Birth of a Nation.

Do you think that Griffith has been sometimes overrated at the expense of other lesser-known film-makers of the time?

Yes, I do. I don’t think he invented all those things that he was supposed to have invented. To suggest he invented the close-up is to deny all the portrait painters since the beginning of painting. Not to mention that the very very first motion picture that you can see is Edison like Fred Ott's Sneeze is in close-up and that’s 1894! And Griffith began directing in 1908. But he did use these techniques extremely effectively. But there are other directors who made marvellous films. Particularly, lost names like Reginald Barker who made The Italian (1915). The early Tourneurs, the early De Milles, Mickey Neilan’s Amarilly of Clothe-Lines Alley (1918) and Stella Maris (1918), the films of John H. Collins and Raoul Walsh’s Regeneration (1915). But also, Griffith was technically highly praised but in fact, could be extremely odd. His editing was unique. He knew narrative editing and that was extremely effective. But continuity editing, cutting from mid-shot to wide-shot. Say, a warrior unsheathing his sword, he does it twice. He overlaps it. Nobody else did that in Hollywood. They immediately got the idea that you make it a smooth transition that makes it almost seamless. So looking back at Griffith work, some of it looks extremely primitive. He’ll suddenly cut to a close-up against pure black in a studio lit, whereas the wide shot is outside! Maddening… And yet, he is undoubtedly brilliant with films like Broken Blossoms (1919), Intolerance (1916), True Heart Susie (1919). Absolutely amazing. And some of the Biographs are superb and stand up wonderfully today. Something like The Knight of the Road (1911) about a tramp in the California fruit farm is brilliant and he did these without script, just knocked them off in a couple of days. Although I remember one of his actresses saying how extravagant he was. So he probably used up a lot of film making them. But I do think..that’s why I’d like to write a book, I’d like to repeat Francis Lacassin’s title an Anti-History of the Cinema [Francis Lacassin: Pour une Contre-Histoire du Cinéma, 1972] and bring forward those directors that have been so overlooked over the years.

For somebody who has never seen any Griffith pictures, which one would you recommend as a starter?

We were shown a beautiful new print of The Lonely Villa (1909) at Pordenone Silent Film Festival, together with the two films that had inspired it [Le médecin du château (Pathé 1908); Terrible Angoisse (Lucien Nonguet, Pathé 1906)]. They would be an ideal start. Then I would go on to another Biograph like The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) or The Unseen Enemy (1912) preferably in an original print off the negative, because they are so superb to look at. And many of the negatives survive. I would definitely start with that and then something like Broken Blossoms (1919). Intolerance (1916) is a crazy film but it’s also a masterpiece, if you have a live orchestra and huge screen, it has tremendous impact.

We were shown a beautiful new print of The Lonely Villa (1909) at Pordenone Silent Film Festival, together with the two films that had inspired it [Le médecin du château (Pathé 1908); Terrible Angoisse (Lucien Nonguet, Pathé 1906)]. They would be an ideal start. Then I would go on to another Biograph like The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) or The Unseen Enemy (1912) preferably in an original print off the negative, because they are so superb to look at. And many of the negatives survive. I would definitely start with that and then something like Broken Blossoms (1919). Intolerance (1916) is a crazy film but it’s also a masterpiece, if you have a live orchestra and huge screen, it has tremendous impact.In 2003, you directed a two-part documentary on Cecil B. DeMille (Cecil B. DeMille: American Epic) covering his silent and talkie period. What made DeMille such an innovative director in the silent era?

The obvious things like dynamic lighting which other people weren’t using so early. I think The Cheat (1915) is as great film as they said it was. The atmosphere is dependent on that extraordinary lighting that he developped. He took a lot from David Belasco but we don’t know what was going on in the theatre at those days so one assumes it all starts in the movies. I am a terrible film critic when it comes to describing these things…There is an energy about those teens DeMille. For a man who was able to shot The Cheat (1915) during the day and The Golden Chance (1915) at night. I mean that is energy. But he puts it in the picture as well. They all those teen films…they’re not too long. They are very well made. They’re beautifully lit, fantastic use of locations, often very interesting themes, especially Kindling (1915). And I think those marital pictures are marvellous too. But, by the time the 20s come, they get awfully silly and yet he is able to direct a film like The Godless Girl (1929) which is brilliant.

The obvious things like dynamic lighting which other people weren’t using so early. I think The Cheat (1915) is as great film as they said it was. The atmosphere is dependent on that extraordinary lighting that he developped. He took a lot from David Belasco but we don’t know what was going on in the theatre at those days so one assumes it all starts in the movies. I am a terrible film critic when it comes to describing these things…There is an energy about those teens DeMille. For a man who was able to shot The Cheat (1915) during the day and The Golden Chance (1915) at night. I mean that is energy. But he puts it in the picture as well. They all those teen films…they’re not too long. They are very well made. They’re beautifully lit, fantastic use of locations, often very interesting themes, especially Kindling (1915). And I think those marital pictures are marvellous too. But, by the time the 20s come, they get awfully silly and yet he is able to direct a film like The Godless Girl (1929) which is brilliant.An important point about DeMille. He wasn’t the sort of innovative director like Eisenstein was by any means. What he established was the future look of Hollywood films. Other directors went along his route rather than imitating Griffith. And his pictures became incredibly overblown and almost ridiculous as they did in the mid-1920s so did the others. But his films of the teens, I find the most interesting.

The French Cinémathèque is organising a DeMille retrospective in April-May 2009. Which films among DeMille silents would you recommend as must see?

The silent films I would recommend for the DeMille season:

The silent films I would recommend for the DeMille season:Certainly The Godless Girl (1929); Why Change your wife? (1920); Whispering Chorus (1918) is an exceptionnal masterpiece, The Little American (1917) is a lot better than you think and it’s also had a great influence on The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921, R. Ingram); Joan the Woman (1917) I suppose ought to be seen, a lot of it is very good; The Heart of Nora Flynn (1916), The Golden Chance (1915), The Cheat (1915) one the most important films of the teens; Kindling (1915). I only stop there because there are so many of them. But The Captive (1915), The Warrens of Virginia (1915), The Girl of the Golden West (1914), What’s his name? (1914) are very good too. All those teens films need to run at 21 fps and The Godless Girl at 24 fps.

DeMille is also a controversial figure for his involvement in the Director’s Guild during the McCarthy era. There was a very tense general meeting in October 22nd, 1950 involving Joseph L. Mankiewicz, then acting director of the Guild, John Ford and all the directors of Hollywood. Could you sum up what happened during this meeting and tell us what you discovered regarding John Ford’s involvement?

As a matter of fact, I can! We interviewed various people for the DeMille film and even before that everybody that was there that I spoke to confirmed the story that DeMille had picked up the list of the 25 directors who had signed the petition to hold this meeting that they were at. And said: “ How interesting some of these names such as Zinnemann, Wilder, Wyler”…and it became one of the standard Hollywood stories when the Director’s Guild of America made a film about themselves, Mankiewicz was interviewed and repeated that story including the wonderful moment when John Ford gets up and says: “My name is John Ford and I make westerns. I admire you Cecil, but I don’t like you.” Now, there are a couple of documentaries coming out and I believe a book, on this subject. And the transcript of the Director’s Guild meeting has also come to light. And I’ve just looked at it and when Cecil DeMille is supposed to pick up the list of names and read them out in that sinister way, he actually doesn’t. What he does is, he reveals, the Communist front organisations that they belong to. But he doesn’t name names. Now, that was a pretty serious thing to do at that McCarthy period, it could lead to people losing their jobs. But as I say, he did not name names. A little later, Rouben Mamoulian gets up and he says a curious thing: “For the first time, I am ashamed of my accent. I always thought I was an American but now I realise..” and I think what has happened is very difficult to explain this clash. It went on for hours and hours. And these men, after all, were story tellers and they did exactly what DeMille did in his history films. They bend history a little bit to make it work as showmanship. So to make the story work, they’ve taken that accent thing from Mamoulian and put it on to DeMille. As a result, we are going to have to change the sequence in the documentary. Does that do it?

Now, John Ford got up and he said: “My name is John Ford and I make westerns.” And he talked about Cecil B. DeMille being…everybody knows his films make more money than anybody else..etc.. “But I don’t like you, Cecil!” And he won the heart of all those directors that were at the meeting. Now, when we were making the film, Cecilia Presley-DeMille, C.B.’s granddaughter, told us that actually her grandfather had received a letter from John Ford, after that meeting, praising his performance and saying what a great man he was. And that’s in DeMille papers at Brigham Young University.

"DEAR MR DE MILLE, I WISH TO HAVE IT FORMALLY RECORDED ON PAPER,WITH MY SIGNATURE ATTACHED, THAT FROM THE SO-CALLED MEMBERSHIP MEETING OF THE SCREEN DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA,YOU EMERGED AS A VERY GREAT GENTLEMAN. YOURS VERY RESPECTFULLY, JOHN FORD"--it was signed in crayon as was his style.

dimanche 14 novembre 2010

Kevin Brownlow Interview (Part IV)

The Parade’s Gone By... and Hollywood

Kevin Brownlow recalls the shooting of the series Hollywood with a host of marvellous anecdotes about the great film-makers and actors he met.

I remember that the attitude of the middle-aged person (some of whom went back that far): “Oh you don’t want to bother about those! They were ludicrously acted, badly photographed, speeded up”…That was the general feeling, there was a really strong attitude against them. Talkies were such a fantastic advance and these were just ludicrous antiques, embarrassing to see now. That was the general feeling. And I went to people’s home, sat them down, put my projector up and always got a terrific thrill out of the way they reacted. They were quite astonished by… “It looks SO MODERN!” Is modern such a compliment?

How easy was it to meet all those directors, actors and technicians? Were they happy to discuss their silent work?

Yes, first of all they were the most extraordinary people I have ever met in my life. They were only a couple of Sunset Boulevard type characters. But those of course are always the colourful ones that ones talks about. What astonished me was how articulate they were, how eloquent they were, how enthusiastic they still were, but how they had been convinced by this black propaganda that silent films were pathetic. So they had no real pride in their work. Again, it was very exciting to meet someone like Reginald Denny, sit him and his family down, show him one of his Universal comedies. And he had no idea they were as good as that. Absolutely no idea.

What was your initial reaction when you were offered to direct a TV series on silent picture?

To run in the opposite direction. I had no interest in TV. I had a very snobbish attitude towards TV. I was a film maker with a capital F and a capital M. And it was my wife who forced me to do it. I just thought it would be like an alcoholic’s cure to go along to a TV company and they would just wreck it and wouldn’t give it enough time, enough money and enough care. And, in fact, exactly the opposite! David Gill turned out to be more rigorous than I was. Just astonishing how much money they spent. They spent a million back in the 70s on that all series. There was no feeling that they were holding back. For instance, they were some difficulties about, for instance, Lillian Gish.

We couldn’t get Lillian Gish to do an interview and finally her manager said: “she’s done her own programme. You’ll have to buy that first.” They did! They spent a lot of money and bought this thing which they showed at one o’clock in the afternoon or something. And then they also paid her substantially. So I cannot say that they didn’t do their damnest to do that series work. The only drawback was that their American distributor sold the series piecemeal. The TV stations had no interest in the series and when the comedy episode went out in LA, they cut Buster Keaton out because a basket ball match was overrunning. And we were told we’d been treated like chopped liver. Now, that had serious consequences because Thames sent David and me out to survey the ground for making a second series on the 30s. And because it had been so badly distributed… It should have been sold to PBS and shown across the nation in one great sweep. We contacted James Stewart and Fred Astaire, all those people, and they’d never heard of the series. What series? So we had nothing to build on and it was never made.

We couldn’t get Lillian Gish to do an interview and finally her manager said: “she’s done her own programme. You’ll have to buy that first.” They did! They spent a lot of money and bought this thing which they showed at one o’clock in the afternoon or something. And then they also paid her substantially. So I cannot say that they didn’t do their damnest to do that series work. The only drawback was that their American distributor sold the series piecemeal. The TV stations had no interest in the series and when the comedy episode went out in LA, they cut Buster Keaton out because a basket ball match was overrunning. And we were told we’d been treated like chopped liver. Now, that had serious consequences because Thames sent David and me out to survey the ground for making a second series on the 30s. And because it had been so badly distributed… It should have been sold to PBS and shown across the nation in one great sweep. We contacted James Stewart and Fred Astaire, all those people, and they’d never heard of the series. What series? So we had nothing to build on and it was never made.How long did it take you to make the 13-episodes Hollywood series with David Gill?

It took 4 years. Can you believe that? For a long time, nothing seemed to be happening at all because the studios ran by the people we’ve been discussing, wouldn’t let us have a frame. And MGM had made That’s Entertainment (1974) and they suddenly realised their vaults were gold mines and “No, we’re not letting anything out on TV.” Then, they made That’s Entertainment II: big flop! Suddenly, the vaults opened up, albeit at great expense. But Thames paid it and we got everything, practically everything we wanted. Even the difficult people, like Goldwyn, they sorted them out and we got The Winning of Barbara Worth (1926, H. King) which I never thought we would get.

You got the opportunity to meet a staggering number of great American directors. Could you tell us something about King Vidor: what kind of a person was he?

Hmmm… Let me tell you another story talking of directors. I was at the Masquer’s club at Hollywood being stood up by the Duncan Sisters and I was waiting and waiting for this… I didn’t particularly want to meet them but they were on in the silent days, they were on the list and a woman said… She saw me looking at a photograph and she said: “Who’s that?” “That’s Fred Niblo.” “Oh yes! Well, you shouldn’t know that!” I said: “I am very interested in silent films and directors;” She said: “Oh! I’m married to one.” I said: “Who?” “Oh, no one you’ve ever heard of: Joseph Henabery.” “Oh my God! Abraham Lincoln in The Birth of a Nation (1915, D.W. Griffith)!” She said: “You’ve heard of him?” (laugh) So she fixed a meeting! I went around to meet Joseph Henabery and there was this tall, very dignified character of whom Bessie Love said had the outlook of Abraham Lincoln. And he was so interesting and so charming. And we had the most fantastic time and I recorded four hours of tape on the first trip. And sometimes, someone like him would recommend another person. But most of the time I had to ring them up, explain who I was and King Vidor I had met way back in the early 60s because Al Parker had told me he was in town. And so he was the first that I went to see after Parker. And he was so easy to talk to, so charming and so fascinating. I got to know him very well. He invited me and my wife to his ranch in Paso Robles and showed us films in the evening and we did the interviews during the day. He took us around the ranch, the streets of which were called Sunset Boulevard, Vine Street… (laugh) He always wore a Stetson. He was a dream to interview. He seemed so youthful.

The directors I suppose were my pets. I remember Raoul Walsh, meeting him in one of those American restaurants that’s terribly dark. They keep them like that for ladies of a certain age. And he was looking at the menu; his Stetson was on the seat, he had cowboy boots, his eye patch. And he was looking at the menu like this. I remember him saying: “Jesus Christ! A guy could go blind in here ordering ham and eggs!” (laugh) They all had the most marvellous way of talking.

The directors I suppose were my pets. I remember Raoul Walsh, meeting him in one of those American restaurants that’s terribly dark. They keep them like that for ladies of a certain age. And he was looking at the menu; his Stetson was on the seat, he had cowboy boots, his eye patch. And he was looking at the menu like this. I remember him saying: “Jesus Christ! A guy could go blind in here ordering ham and eggs!” (laugh) They all had the most marvellous way of talking.Byron Haskin is a typical example. If you ask an Englishman, how hot were the lights on the set? They’d say: “Oh! Very hot.” Well it’s informative, you know where you are. But these fellows had the Irish way of talking. And Byron Haskin said: “Hot!!! Jesus! You could light a cigar on a beam at a hundred yards!” (laugh) Fabulous!

William Wellman appears like an extremely energetic character when he describes the shooting of Wings. Did he really deserve his nickname ‘Wild Bill’?

Oh yes! He was really something in his youth. He was a juvenile delinquent. And he said: “The trouble was my probation officer was my mother.” (laugh) He would pinch cars and go for joy rides. That’s the reason why he went to the Lafayette Flying Corps, a way to get rid of him! He was again absolutely like somebody out of the old west. I don’t think he told the truth. Howard Hawks was the most difficult one. Nonetheless Wellman was mesmerizing.

I’m trying to think of the ones that were really difficult. There was one called Nick Grinde who made B pictures and he just played with me when I was trying to interview him and wouldn’t answer properly. But the rest of them were so enthusiastic, and obviously still in love with the movies…and another one we liked very much was Edward Sloman. But when I first interviewed him and asked about his films, he’d say: “Oh yes! I EARNED 17,000 $ a week on that one!” (laugh) and then you asked him about this other film and “25,000 $ a week!!!” (laugh)

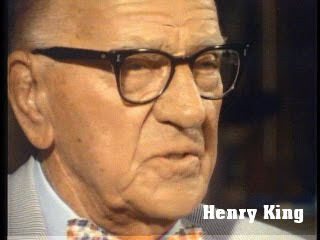

Henry King is also featured prominently in your series.

Oh my God! He was a biblical character. Very tall, very handsome, incredibly dignified with a charisma I cannot describe to you. When he was talking to you, you were lost in what he was saying. And we were so impressed that we can back and shot him again the following day, and again. And sent the rushes back and the word came through: adequate. Ok. Because charisma doesn’t transfer itself to celluloid which why of course people employ actors. He was an actor but as a man, he had fantastic charisma and it just doesn’t come across at all on the film. And that was a tremendous disappointment.

Oh my God! He was a biblical character. Very tall, very handsome, incredibly dignified with a charisma I cannot describe to you. When he was talking to you, you were lost in what he was saying. And we were so impressed that we can back and shot him again the following day, and again. And sent the rushes back and the word came through: adequate. Ok. Because charisma doesn’t transfer itself to celluloid which why of course people employ actors. He was an actor but as a man, he had fantastic charisma and it just doesn’t come across at all on the film. And that was a tremendous disappointment.The man the crew chose as the most impressive of all was a man confined to a wheelchair that’d had a severe stroke and could hardly talk. And that was Lewis Milestone.

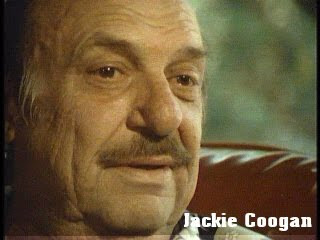

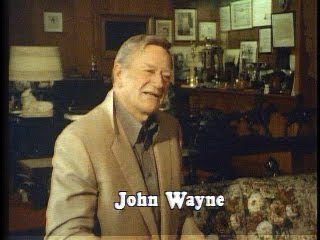

Some people gave some very emotional testimonies in this series. I am thinking of Janet Gaynor as she recalls being directed by Murnau in Sunrise or Jackie Coogan describing the shooting of the most dramatic scene in The Kid. There is also John Wayne, his eyes misty with tears, recalling his late friend Harry Carey Sr. How did you manage to get such testimonies from them?

Yes! That’s very interesting!

Janet Gaynor was a naturally emotional person. She probably hadn’t talked about it for decades and suddenly she was talking about the most important moments in her life. And it was very moving just to sit there and hear all this amazing description of shooting one of these legendary films.

Now Jackie Coogan was a different matter. Jackie Coogan was delivering perfectly satisfactorily. I had not seen The Kid in a proper version. I had seen pirate prints. I had not been impressed. David had just seen the proper version of The Kid and had been tremendously impressed and he knew I wasn’t getting out of Jackie Coogan what I should be getting. So he kept stopping the camera, coming down and talking to Jackie more and more…and Coogan realised he was being reminded of the film. And David got that choked up reaction from him. Then I was back to London and saw The Kid and thought: “My God!” I saw what David had seen and was knocked out by The Kid. And I wished I’d seen that before. It would have made such difference. If you admire somebody tremendously, there is something unsaid in the way you talk to them. And that wasn’t happening in my case with Coogan.

Now Jackie Coogan was a different matter. Jackie Coogan was delivering perfectly satisfactorily. I had not seen The Kid in a proper version. I had seen pirate prints. I had not been impressed. David had just seen the proper version of The Kid and had been tremendously impressed and he knew I wasn’t getting out of Jackie Coogan what I should be getting. So he kept stopping the camera, coming down and talking to Jackie more and more…and Coogan realised he was being reminded of the film. And David got that choked up reaction from him. Then I was back to London and saw The Kid and thought: “My God!” I saw what David had seen and was knocked out by The Kid. And I wished I’d seen that before. It would have made such difference. If you admire somebody tremendously, there is something unsaid in the way you talk to them. And that wasn’t happening in my case with Coogan. Now, John Wayne was on a glass that size full of colourless liquid at 10 o’clock in the morning. And he started directing. He said: “I tell you what we do. See this bronze? We start down here and we move back up..” And the cameraman said: “ No, no, no, we don’t do anything like that!” (laugh) He was furious and walked out and I had to rush next door and plead with him to come back on the set. “Say! You know..” and his collar was turned up, he was fighting with it, when the camera was on him. Turn over; you could almost hear an orchestra start up. He was a different man. He was so charming and he not only told the story that you see in the film about The Searchers (1956, J. Ford), which had me choked up as well as he was telling it, but he told the most wonderfully funny stories about the making of The Big Trail (1930, R. Walsh). And he imitated Tyrone Power Sr. That was so funny. I wished we’d used it! But in the end, he was arm in arm with the cameraman. He looked at his bracelet and he said: “Ah! You’ve been in Vietnam!” (laugh) and they were on each other’s neck from that moment…(laugh)

Now, John Wayne was on a glass that size full of colourless liquid at 10 o’clock in the morning. And he started directing. He said: “I tell you what we do. See this bronze? We start down here and we move back up..” And the cameraman said: “ No, no, no, we don’t do anything like that!” (laugh) He was furious and walked out and I had to rush next door and plead with him to come back on the set. “Say! You know..” and his collar was turned up, he was fighting with it, when the camera was on him. Turn over; you could almost hear an orchestra start up. He was a different man. He was so charming and he not only told the story that you see in the film about The Searchers (1956, J. Ford), which had me choked up as well as he was telling it, but he told the most wonderfully funny stories about the making of The Big Trail (1930, R. Walsh). And he imitated Tyrone Power Sr. That was so funny. I wished we’d used it! But in the end, he was arm in arm with the cameraman. He looked at his bracelet and he said: “Ah! You’ve been in Vietnam!” (laugh) and they were on each other’s neck from that moment…(laugh)Among the technicians featured in your series, there are quite a few cinematographers. I was particularly impressed by Karl Brown and Paul Ivano who gave some very interesting insights on working with D.W. Griffith and Erich von Stroheim. How did you find them?

When I was in the AFI, I received a message from the MoMA. Is Karl Brown still alive? And I replied: “No, if he was, I’d know!” because I’ve always wanted to meet him. Well, thank God, they didn’t take my word for it. They rang a fellow George J. Mitchell who was a military intelligence officer during the war and he did the obvious thing, he looked in the telephone book and there was a Karl Brown. He hadn’t had time to follow this up, so he rang me. It was a bit embarrassing; having said that the man isn’t alive and being told that he is! (laugh) OK I went over to that address and he’d left. The landlord said he’d gone with his wife and he had no idea where. So now began, I think it took 6 weeks, in which we did everything we could to find this man. We even stopped old men on the street and said: “You weren’t in the picture business, were you?” And they replied: “No, I was in Wall Street. I can tell you all about it!” “Yes, thanks very much!” (laugh) And it was an extraordinary period. We searched various bureaus downtown, the death certificates and everything else. And I can’t remember whom I was interviewing, but I was interviewing somebody. And the telephone kept ringing and I kept putting them off. It was actually somebody telling me that the department of motor vehicle had left a message and the message was Karl Brown’s address! So that night my wife and I got into her Volkswagen and we went along Laurel Canyon. It was very very misty and it was like going back in a H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. The trouble with LA, a road would go along and then it would be blocked off with lots and lots of buildings, and then starts again and it gets block off. It’s terribly difficult to find it. The numbers are endless, you know. We eventually found it and the bungalow was completely dark. I knocked on the door and nobody came. Anticlimax! I was just leaving when I saw an extraordinary thing. I saw a motion picture on the wall in colour. Then I saw the credits and credits were rolling backwards and I realised it was a picture on the wall, reflecting the television set, a colour TV set which was beneath the window. So I knocked and I rang. And eventually shuffle, shuffle, the oldest old woman you ever saw in your life came to the door. I said: “Does Karl Brown live here?” “How did you find us?” Shuffle, shuffle and then she came back and said: “He’ll see you!” And in I went, to another part of the house and there was Karl Brown, sitting in an armchair, as though he’d been waiting. And he just switched on like that as though he’d been interviewed everyday for a year. And he started talking about Griffith, The Birth of a Nation, Intolerance…Unbelievable! I kept going back and interviewing him some more. Every time it was gold dust! I finally persuaded him to write his book because I saw that he was a writer. And he did! He produced a fabulous book which was published as Adventures with D.W. Griffith. And then he went on and he wrote another one. But unfortunately the publisher of Adventures with D.W. Griffith got in touch with him separately and told him not to write more than 30,000 words. And for the first book, he’d written lots more. It was easy to take it out, but the information was saved. But in the second one, The Paramount Adventure, he just wrote what was required and so an awful lot has been lost. He also wrote one on Monogram. Anyway, he was one of the richest sources. And I came to him through a film I discovered at the Czech film archives in 1968 when Andrew and I went over, just after the Russian had invaded it. And Myrtle Frieda, the head of the archive showed us his favourite American silent which was Stark Love (1927) and I wrote an article about that. And that lead to the film being rescued by the MoMA. I think out of all the films that appeared in the Hollywood series, the one with the finest quality was The Covered Wagon (1923, James Cruze) photographed by Karl Brown in which we have many magnificently photographed films, but just for sheer guts, the image quality was stunning.

When I was in the AFI, I received a message from the MoMA. Is Karl Brown still alive? And I replied: “No, if he was, I’d know!” because I’ve always wanted to meet him. Well, thank God, they didn’t take my word for it. They rang a fellow George J. Mitchell who was a military intelligence officer during the war and he did the obvious thing, he looked in the telephone book and there was a Karl Brown. He hadn’t had time to follow this up, so he rang me. It was a bit embarrassing; having said that the man isn’t alive and being told that he is! (laugh) OK I went over to that address and he’d left. The landlord said he’d gone with his wife and he had no idea where. So now began, I think it took 6 weeks, in which we did everything we could to find this man. We even stopped old men on the street and said: “You weren’t in the picture business, were you?” And they replied: “No, I was in Wall Street. I can tell you all about it!” “Yes, thanks very much!” (laugh) And it was an extraordinary period. We searched various bureaus downtown, the death certificates and everything else. And I can’t remember whom I was interviewing, but I was interviewing somebody. And the telephone kept ringing and I kept putting them off. It was actually somebody telling me that the department of motor vehicle had left a message and the message was Karl Brown’s address! So that night my wife and I got into her Volkswagen and we went along Laurel Canyon. It was very very misty and it was like going back in a H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. The trouble with LA, a road would go along and then it would be blocked off with lots and lots of buildings, and then starts again and it gets block off. It’s terribly difficult to find it. The numbers are endless, you know. We eventually found it and the bungalow was completely dark. I knocked on the door and nobody came. Anticlimax! I was just leaving when I saw an extraordinary thing. I saw a motion picture on the wall in colour. Then I saw the credits and credits were rolling backwards and I realised it was a picture on the wall, reflecting the television set, a colour TV set which was beneath the window. So I knocked and I rang. And eventually shuffle, shuffle, the oldest old woman you ever saw in your life came to the door. I said: “Does Karl Brown live here?” “How did you find us?” Shuffle, shuffle and then she came back and said: “He’ll see you!” And in I went, to another part of the house and there was Karl Brown, sitting in an armchair, as though he’d been waiting. And he just switched on like that as though he’d been interviewed everyday for a year. And he started talking about Griffith, The Birth of a Nation, Intolerance…Unbelievable! I kept going back and interviewing him some more. Every time it was gold dust! I finally persuaded him to write his book because I saw that he was a writer. And he did! He produced a fabulous book which was published as Adventures with D.W. Griffith. And then he went on and he wrote another one. But unfortunately the publisher of Adventures with D.W. Griffith got in touch with him separately and told him not to write more than 30,000 words. And for the first book, he’d written lots more. It was easy to take it out, but the information was saved. But in the second one, The Paramount Adventure, he just wrote what was required and so an awful lot has been lost. He also wrote one on Monogram. Anyway, he was one of the richest sources. And I came to him through a film I discovered at the Czech film archives in 1968 when Andrew and I went over, just after the Russian had invaded it. And Myrtle Frieda, the head of the archive showed us his favourite American silent which was Stark Love (1927) and I wrote an article about that. And that lead to the film being rescued by the MoMA. I think out of all the films that appeared in the Hollywood series, the one with the finest quality was The Covered Wagon (1923, James Cruze) photographed by Karl Brown in which we have many magnificently photographed films, but just for sheer guts, the image quality was stunning. Paul Ivano must have been recommended by Robert Florey. He was a friend of Florey. He was quite surprising. He was a Serb and he served in the French Army during WWI. He was used as a technical adviser on The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921, R. Ingram) and he worked with most interesting characters but the most interesting was Erich von Stroheim and he told us with no sense of shame what went on that picture…(laugh) Our eyes were on stalks! I’ll tell you an odd thing. He lived with Valentino and Natacha in a sort of strange ménage à trois. And you remember this funny: “ahaha!” every time he would say something, he’d go “ahahaha!” and he said: “ahahaha! I haven’t seen him for quite a while.” He died in 1926, I think. I said: “What do you mean?” He said: “I saw him just recently. Ahaha!” “Who?” “Valentino! He appeared here!” “Oh!” (laugh) He was seeing Valentino…(laugh) very worrying…

Paul Ivano must have been recommended by Robert Florey. He was a friend of Florey. He was quite surprising. He was a Serb and he served in the French Army during WWI. He was used as a technical adviser on The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921, R. Ingram) and he worked with most interesting characters but the most interesting was Erich von Stroheim and he told us with no sense of shame what went on that picture…(laugh) Our eyes were on stalks! I’ll tell you an odd thing. He lived with Valentino and Natacha in a sort of strange ménage à trois. And you remember this funny: “ahaha!” every time he would say something, he’d go “ahahaha!” and he said: “ahahaha! I haven’t seen him for quite a while.” He died in 1926, I think. I said: “What do you mean?” He said: “I saw him just recently. Ahaha!” “Who?” “Valentino! He appeared here!” “Oh!” (laugh) He was seeing Valentino…(laugh) very worrying…I think you are very fond of cinematographer John F. Seitz. Nowadays, he is mostly remembered for his work with Billy Wilder on Sunset Boulevard and Double Indemnity. But, his silent career was also impressive with Rex Ingram’s Scaramouche and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. What innovations did he bring to cinematography?

Oh God! He changed the look of American pictures and he had a number of followers, Byron Haskin, a cameraman was one. And you can see in Don Juan and the Warner Brothers pictures that Haskin photographed, a tremendous debt to Ingram and Seitz. There is a lovely story in the Hollywood series about Seitz is his low-key lighting and the lab man would come along to look at his set, worrying about the thinness of the negative: “OK, you can switch the lights on now, John!” “They are on!” (laugh) He was strange man. He seemed very nervous and really shook up in his old age, but, he insisted on driving. And he drove up to the AFI, we had a long interview. And then went off again. And fade out. Fade in. In came an angry fellow from the AFI, he said: “Was that fellow in the Cadillac connected with you?” I said: “What? John Seitz? Yes, why?” He hit six cars going out of the estate and I had to pay for it! (laugh)

But what was marvellous was that John Seitz put me in touch with Alice Terry. She was a recluse really. But I rang her up, mentioned this reassuring name and that I was going to run The Conquering Power (1921, R. Ingram) and would she like to see it? I thought she’d refuse and she said: “Could I bring my sister?” (laugh) So they turned up, Alice Terry, her sister, the cameraman Seitz, the editor Grant Whytock, and several other people from the Ingram crowd. They all gathered and saw this fascinating film. And they all opened up and we were invited back to Alice’s place many many times. The only thing she wouldn’t do was to appear on the Hollywood programme. It was really upsetting because we really needed her. To think that she was there and wouldn’t do it. But she was concerned with the weight she’d put on.

Louise Brooks discusses her friend Clara Bow with enormous warmth though she never mentions her own work. Did she still despise Hollywood as a whole?

No she loved it. She was writing about it as much as she could. She was researching Wellman, and researching Mal St. Clair and she wrote a whole series of articles for Sight & Sound. First of all, how do we get her to do it? I knew she was going to be very very difficult. So we brought Bessie Love over. And when Louise heard that Bessie Love was with us, she agreed we could come on over. And so we flew up to Rochester and she was thrilled to meet Bessie Love. That put her in a great good humour and yes, she’d do it. So we set up and we got the cameraman and the sound recordist in this tiny apartment. And Louise was firing on all cylinders talking about Clara Bow. Because she was very angry that I hadn’t included Clara Bow in my book which was pure oversight because I was mad about Clara Bow. She’d done that part and we getting her on her own work and suddenly the sound recordist took off his earphones and said: “CUT! Sounds like a bathroom in here!” And that put her in such a bad temper that we couldn’t use the rest of the interview. She was growling it out. The sound recordist does not cut the scene! I could have killed him…

No she loved it. She was writing about it as much as she could. She was researching Wellman, and researching Mal St. Clair and she wrote a whole series of articles for Sight & Sound. First of all, how do we get her to do it? I knew she was going to be very very difficult. So we brought Bessie Love over. And when Louise heard that Bessie Love was with us, she agreed we could come on over. And so we flew up to Rochester and she was thrilled to meet Bessie Love. That put her in a great good humour and yes, she’d do it. So we set up and we got the cameraman and the sound recordist in this tiny apartment. And Louise was firing on all cylinders talking about Clara Bow. Because she was very angry that I hadn’t included Clara Bow in my book which was pure oversight because I was mad about Clara Bow. She’d done that part and we getting her on her own work and suddenly the sound recordist took off his earphones and said: “CUT! Sounds like a bathroom in here!” And that put her in such a bad temper that we couldn’t use the rest of the interview. She was growling it out. The sound recordist does not cut the scene! I could have killed him…Gloria Swanson still looked stunning when you filmed her. She comes through as a very strong personality. How was she as a person?

I knew Gloria Swanson from London. She was very difficult to get hold of. I was given her telephone number and I rang it. And I gave my usual pitch, how interested I was in her. “Do you mind?” How fascinated I was. “Do you mind?” (laugh) So I had to go through somebody else. And eventually I got to meet her and we got on like a house on fire. In fact, I was going to make a film for her, two films for her. I was going to make film about Queen Kelly for the BBC and that was blocked by the man who’d made I Claudius. He says: “If that film is made. I’ll direct it! You don’t.” And the other thing I was going to do was something about a religious woman she wanted a film made about. She tried to get me to do that.

I knew Gloria Swanson from London. She was very difficult to get hold of. I was given her telephone number and I rang it. And I gave my usual pitch, how interested I was in her. “Do you mind?” How fascinated I was. “Do you mind?” (laugh) So I had to go through somebody else. And eventually I got to meet her and we got on like a house on fire. In fact, I was going to make a film for her, two films for her. I was going to make film about Queen Kelly for the BBC and that was blocked by the man who’d made I Claudius. He says: “If that film is made. I’ll direct it! You don’t.” And the other thing I was going to do was something about a religious woman she wanted a film made about. She tried to get me to do that.She had a front which was the Great Star. If I said Norma Desmond I wouldn’t be far wrong. She was haughty, difficult to talk to, snobbish, all the things you didn’t want her to be. But it was just a front and once you’d gone through that, she was like a tomboy. She suddenly became very funny, really charming and terrific! So long as you could keep that first thing at bay. But then long gaps, in which she’d go back to that. It was very difficult getting that interview and we had to pay an awful lot of money. She was one of the last people to surrender. And I thought of every question I could possibly ask her. What I never realised was she would be on the same programme as Valentino. And I forgot to ask her about Beyond the Rocks (1922, S. Wood). And then I comforted myself by saying well Beyond the Rocks is a lost film. We should have covered it. We didn’t but nobody will know because the film will never be discovered. (laugh) And then of course, it was! Very unfortunate…

But it was a tremendous interview and there’s much more there than we used, obviously and she was suggesting that she wouldn’t be surprised if William Desmond Taylor was not shot by orders of Paramount Pictures. There’s a conspiracy theory for you!

samedi 13 novembre 2010

Kevin Brownlow Interview (Part III)

You already told us how you saw for the first time some fragments of Napoléon. Why did it capture so much your imagination?

I told you how fascinated I became with military history, I think, through my father who was always talking about and later through Andrew Mollo. But this was before that, before I met Andrew, this was 1954 or 53, something like that. I thought it looked like an 18th century newsreel. It was so authentic. But the camera did things I have never seen it do before. For example there is an amazingly bold intercutting of a storm. Napoléon is escaping from Corsica, has taken a dinghy and got caught in a tempest and at the same time, in the Convention, the Jacobins are turning on the Girondins. And Gance had the idea of combining these two events and intercutting them. And it is astounding! Taking the phrase from Victor Hugo: to be a member of the Convention was to be a wave on the ocean. He puts the camera on a pendulum and swings it over the Convention which is in riot and then you intercut this waves crashing on top of Napoleon’s tiny boat. And then hand-held camera shots among the crowd fighting in the Convention, gives you a sort of sea-sick feeling. Anyway, it’s just astounding! Napoléon has more innovative ideas in it than any film ever made before or since. And quite of lot of them have never been followed up. And that’s one them. When it was shown first here in 1980, the director Alan Parker scrapped footage that he had been shooting for a film called Pink Floyd: The Wall and he put the camera on a pendulum. (laugh)

What was the status of Abel Gance among film lovers and critics at that time? Nobody had heard of him. When I first started showing this film, I had never heard of him. And I just became a propagandist for him. I must say that film makers responded very strongly when they saw the footage or even a hint of the footage. But I have never known anything like the first night at the Empire Leicester Square when the whole thing was shown. I remember coming out of the Leceister Sq tube feeling absolutely terrified. Number one, how could the orchestra stay in synch for 4h and 50min? How could the audience sit there for all that time? It just wasn’t going to work. But the moment, it caught everybody was the end of the Brienne sequence, when Napoléon is on a cannon and the eagle returns. And Carl Davis’ magnificent Napoleon theme crashes out over the…The audience was staggered. And I remember Jeremy Isaacs saying if this isn’t shown on Channel 4, there won’t be a Channel 4. because he was going to be the head of it. I’ve never known an experience like that. Whenever it’s shown, people come up to me afterwards and say: “it’s changed my life”. That’s the most common phrase I’ve heard. It goes back to that feeling that I would much rather show a masterpiece by somebody else that I feel a 100% enthusiasm for than one of my own films that I can see all the faults in.

Nobody had heard of him. When I first started showing this film, I had never heard of him. And I just became a propagandist for him. I must say that film makers responded very strongly when they saw the footage or even a hint of the footage. But I have never known anything like the first night at the Empire Leicester Square when the whole thing was shown. I remember coming out of the Leceister Sq tube feeling absolutely terrified. Number one, how could the orchestra stay in synch for 4h and 50min? How could the audience sit there for all that time? It just wasn’t going to work. But the moment, it caught everybody was the end of the Brienne sequence, when Napoléon is on a cannon and the eagle returns. And Carl Davis’ magnificent Napoleon theme crashes out over the…The audience was staggered. And I remember Jeremy Isaacs saying if this isn’t shown on Channel 4, there won’t be a Channel 4. because he was going to be the head of it. I’ve never known an experience like that. Whenever it’s shown, people come up to me afterwards and say: “it’s changed my life”. That’s the most common phrase I’ve heard. It goes back to that feeling that I would much rather show a masterpiece by somebody else that I feel a 100% enthusiasm for than one of my own films that I can see all the faults in.

Can you tell us about your first meeting with Abel Gance? I met a journalist called Francis Koval and he produced triptychs showing what the ending looked like. And he’d met Abel Gance and he lent me a photograph of him. I showed it to my friend Liam O’Leary who was the deputy curator at the NFT. And later on, he was looking through the door of his office at the BFI and he saw that man standing in the hall! He went out and in his execrable Irish accented French: “Etes-vous monsieur Gance?” He was amazed to be recognised because he’d flown over to see Cinerama at the Casino Theatre in London. He was walking down Shaftsbury Avenue and he saw a sign saying British Film Institute and he could understand that, so he walked in. He was amazed to be recognised. Liam rushed off to tell James Quinn who was the director who said: “Give him a reception!” And so I was telephoned by my mother at school and the only reason you ever telephone someone at school is if a relative had died. So I was allowed to answer the phone, I was taken out of an exam, mock school certificate in German. My mother said: “Come home at once!” So I rushed home and she told me that Liam had met Gance. Gance was in London. I was going to meet him that afternoon. It was unbelievable. So I grabbed the script –I had bought the script by then- which had been published in France and a couple of stills and rushed off to the NFT and met my hero who was, you can imagine, he looked magnificent, looked like a medieval saint I think…he was so exuberant, enthusiastic and amusing even though I didn’t speak French. We somehow understood each other and it was an amazing event. And that was the beginning of my obsession with Napoléon which still goes on. That was 1954; it was 54 years ago. My God!

I met a journalist called Francis Koval and he produced triptychs showing what the ending looked like. And he’d met Abel Gance and he lent me a photograph of him. I showed it to my friend Liam O’Leary who was the deputy curator at the NFT. And later on, he was looking through the door of his office at the BFI and he saw that man standing in the hall! He went out and in his execrable Irish accented French: “Etes-vous monsieur Gance?” He was amazed to be recognised because he’d flown over to see Cinerama at the Casino Theatre in London. He was walking down Shaftsbury Avenue and he saw a sign saying British Film Institute and he could understand that, so he walked in. He was amazed to be recognised. Liam rushed off to tell James Quinn who was the director who said: “Give him a reception!” And so I was telephoned by my mother at school and the only reason you ever telephone someone at school is if a relative had died. So I was allowed to answer the phone, I was taken out of an exam, mock school certificate in German. My mother said: “Come home at once!” So I rushed home and she told me that Liam had met Gance. Gance was in London. I was going to meet him that afternoon. It was unbelievable. So I grabbed the script –I had bought the script by then- which had been published in France and a couple of stills and rushed off to the NFT and met my hero who was, you can imagine, he looked magnificent, looked like a medieval saint I think…he was so exuberant, enthusiastic and amusing even though I didn’t speak French. We somehow understood each other and it was an amazing event. And that was the beginning of my obsession with Napoléon which still goes on. That was 1954; it was 54 years ago. My God!

Why are they so many different versions of Napoléon?

God! First of all, he made a film which was going to be shown over several days, now the film of episodes was reasonnably strong tradition. Les Trois Mousquetaires, Les Misérables, all these things were films of episodes which would be coming out over several weeks. But for some reasons, exhibitors objected to Napoléon being a film of episodes and tried to shorten it. And they started arbritarily taking out bits and I’ve noticed whenever Napoléon gets sent abroad, people get creative. (laugh) They want to fiddle around with it, to alter it. Bob Harris and Francis F. Coppola, when they showed it in America, it had to be cut down to fit a slot at the Radio City Music Hall. They then said they’d show the whole thing which they reneged upon. They never did. When Bambi Ballard did try to do the French Cinémathèque version, she decided it was going to have its triptych back in the middle, even though it didn’t exist. She got Jean Dréville, who said he remembered it from 1927, to recut it and thus I think lost the impact of one of the great sequences which is the double storm which in its single screen version is a masterpiece of editing. I’m sure it looked very impressive in triptych when it was shown in the short version but ended part one, act one. You can’t then go back to the single screen as happens now in the French version, because that’s tremendously anticlimactic and against the rules of showmanship. But you know it’s maddening…The most upsetting thing is the fact that the French score is so unfortunate.

What made you move from collecting fragments of Napoléon to actual restoration of the film?

I decided that Abel Gance was so little known in England that I ought to make film about him. So I made the documentary entitled The Charm of Dynamite for the BBC in 1968. When I was making that Gance told me that he had shot footage of the film being made. I already thought he was suffering from dementia because at that point, there wasn’t any footage of any film being made. You just didn’t see that sort of thing so I thought he was pretending he’d done something fantastic and he hadn’t done it at all. I mention this to Marie Epstein from the Cinémathèque and she went out to a vault and came back with a pile of rusty cans, put them down and went out for more. I couldn’t resist looking inside this can. The first can, there was a large roll and I took it out and looked at it. And I suddenly realised that this was the famous snowball fight that in that book by Bardèche & Brasillac, it talks about this great sequence which is a masterpiece of rapid cutting. So when she came back, she was a bit annoyed to see me looking at it, having taken it out of the can. She good-naturally put it on the viewing machine and I count that as one of the great moments of my life, to suddenly see this long lost sequence. So brilliantly done, I couldn’t believe it, I was absolutely sweating by the end of it. My eyes were on stalks. And then Gance said: “You found that! The snowball fight! Can you get it for me?” (laugh) I thought: “Oh My God! This is the man who made the picture!” He said: “I can’t get anything out of the Cinémathèque. You need one revolver for Henri Langlois and one for Mme Epstein.” (laugh) So, from London, I ordered two copies and sent one to Gance and used the other for the first step in the restoration. I thought this is the beginning. And that went into the film first. And the next thing that happened was George Dunning, who made The Yellow Submarine the animated film with The Beatles, put on a wide-screen festival in London. And he independently requested the triptychs from Napoléon and got them over without any trouble (I am sure they were the original prints), projected them at the Odeon Leceister Square with three projectors and when they had to go back, he did the sensible thing and he copied them and gave me the negative to look after. So I thought this is another sign from above, here I go step by step. I have now the triptych ending, the snowball fight and David Meeker who worked at the BFI told Jacques Ledoux who was then head of FIAF. And Ledoux took it upon himself to contact all the archives and said: “If you’ve got anything of Napoléon, send it to KB care of the BFI.” And the stuff flooded in. And it was in 1968 or something, and that’s when I started putting the film together.

How easy was it to work with the French Cinémathèque at the time?

Very tricky. I mean if the French Cinémathèque, at the time, had cooperated –they had all the footage- I didn’t need to get it from all the way around the world. They had it all. Except, Gance gave them the hostages at Toulon being executed which would have been one of the most majestic sequence ever. And they lost it or it was destoyed in the fire.

Let’s talk about a real problem with silent pictures: projection speed. How do you determine the proper projection speed between 16 fps and 24 fps for a silent picture?

This is a nightmare, an absolute nightmare! But there is a rule of thumb, in America, practically nothing went at 16 fps except newsreels and Griffith films. For some reason, Griffith liked to crank very slowly. We found recently doing the DeMille documentary, that The Squaw Man which started production in 1913 was shot at 21 fps. So they were much faster quite early. By the 20s, most American pictures were going at 20 fps and upwards. When it came to the mid-20s, MGM pictures were nearly all shot at 22 fps. They are all shot at 22 fps, then projected at 24 fps. All silent films are projected with the edge off which is why people found sound films to be in slow motion until they got used to them. To get that speed, the Vitaphone engineers went round the big Broadway theatres and got the average speed. They discovered that in 1925, the average speed of Broadway theatres was 22 to 26 fps. So they chose 24 fps. In the British Isles, we went much slower, so did you. The French by the 20s, were going at an average of 20 fps. But the British managed to stay at 16 and 18 for ages. You sometimes find them right up to the coming of sound being projected at ridiculously slow speeds. However projectionists raced both over there and here. They wanted to get home quicker. And they would just speed up! And there were an awful lot of objections to that. That is one reason why the Americans speeded up so quickly. But the secret of the universe if you are watching an American film –it doesn’t always work for continental ones- but if you watch an American picture, you see a title, you read it at normal speed twice almost and just as get to the last word, it should be snatched off. That means the picture is running at the right speed.

Can you recall your impressions when you first saw on a big screen at the Telluride Film Festival (in 1979) your reconstruction of Napoléon with the triptych?

Do you know? I have absolutely no memory of my being impressed by the triptych at Telluride! Probably because we were frozen to death. And I was so worried about the ghastly experience I had with Gance on the stage. I remember being terribly impressed with it in the Empire Leicester Square. That was the time when it knocked me out.

Can you tell us about your work with the composer and conductor Carl Davis? How did you meet him?

When I joined Thames Television to makes this programme, I was very nervous about who I was going to partnered with. Because they first introduce me to a producer who sais to: “You are interested in silent films, aren’t you?” “Yes, I am.” “I just want to let you know I can’t stand silent films.” Luckily he was off the project very quickly and I got David Gill who could not have been more enthusiastic. But who were we going to get to write the music? The music was the most essential thing because a 13h programme really…If you got the wrong man…Well, I had been very impressed by the title music particularly of The World at War (1974). And Jeremy Isaacs gave us that composer Carl Davis. He came from America, from NY. So he already was of that world. He went back and interviewed as many silent film musicians as he could find to get advice. And he really does seem to…it seems to get a natural response his reactions to the film. He could have been there himself I always thought. The first thing he did was Ben-Hur (1925, F. Niblo) for a promotion to try to sell the series in America and I remember being tremendously excited going along to a recording studio with a big orchestra playing the chariot race flat out. That I had never heard anything like that because on the film of the 1931 reissue of Ben-Hur which has the original score, the music has been taken off for the chariot race and put pounding hooves all the way through it which doesn’t help it at all. So we worked with Carl on practically every documentary and many of the Thames Silents. The last one he did is The Godless Girl (1929, C.B. DeMille).

How do you compare his score for Napoléon with that of Carmine Coppola?

I think that Carl’s score, it has tremendous emotion. And I miss that in the Coppola version which does include some marvellous pieces by composers like Mendelssohn. But it simply doesn’t have the emotional quality. And I remember when we saw it at Radio City Music Hall, it got laughs in the wrong places which it certainly doesn’t get in London. People have tears in their eyes when Dieudonné sees his mother. When you see the Coppola version, people giggle and that suggests he hasn’t got it right.

Through the years, there have been many legal problems which prevented your 5 ½ hours version of Napoléon (with the Carl Davis score) to be released on DVD. I understand that the French Cinémathèque has its own version with a Marius Constant score. Where are we now? Are the problems going to be resolved soon?