Part 2

French Silents

French Silents

I wanted to discuss this forgotten era of French cinema with Kevin Brownlow as I knew he felt passionately about it. He also talked about the influence of French directors on American film in the teens, particularly that of Maurice Tourneur. He also tells us how he discovered Gance's Napoléon.

What happened was that I was looking for old films and I got as far as Paddington. I was in Praed Street and a photographic shop had a print of a film called Fishers of the Isle. I had no idea what it was. It was about 12 shillings and sixpence and I brought it home. And it was the most exquisite picture: Pêcheur d’Islande (1924) by Jacques de Baroncelli and I showed it to my mother. She was completely smitten with French culture; in fact at one time, she nearly married a Frenchman. She loved it and said: “It’s the most beautiful film you’ve got!” And, it was shot in Brittany. It starred Charles Vanel and Sandra Milowanoff and I thought it was superb. I still think it’s superb. I cannot understand why it’s buried in the CNC because they’ve got a beautiful print right off the camera negative. The only thing wrong with it, because they were short of money, the storm sequence is done rather badly and you see a model yacht floating in a bath, you know that sort of effect. But otherwise, it’s flawless, beautiful. So that made me look for more French silents and particularly those provincial silents shot on locations like La Terre for instance. I found those absolutely marvellous. I couldn’t find enough and that was why I made one myself. It’s absolutely ludicrous to have made a French film in Hampstead (laugh) because the whole point of these was their authenticity, the fact that they were shot on locations…however that was why I made Les Prisonniers as it eventually was called. But one French film I did get after a while was called The Lion of the Mogols (Le Lion des Mogols, 1924, J. Epstein). And it was dreadful. It was so bad I couldn’t bear having it around so I rang up the library I got it from in Bromley and said could I exchange it? That was 2 reels, no it was 1 reel I think, and they said that all they had was a film called Napoleon Bonaparte and The French Révolution. I thought this is going to be a classroom film with static engravings and long text titles. I said I’ve got to get rid of The Lion of the Mogols so I’ll go for it. And I’ll send this one back. And when the Napoléon film arrived I was at home with flu from school. And I got the projector up and got my parents into the front room. And it was the cinema as I always thought it ought to be: tremendously ambitious, spectacular, innovative, the camera doing things I’ve never seen it do before and my mother then said: “That’s the most beautiful film you’ve got!” (laugh) and I discovered that it was part of a 6 reel release. Then I put advertisements in the magazine the Exchange & Mart and said I wanted Napoléon and I did get eventually the whole thing as it was released on 9.5 mm and people came round to see it. I remember David Robinson, who is now the director of the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, being brought by Liam O’Leary from the BFI. He came to see it in the 50s. And it lasted 6 reels, around one hour and a half. And that led to something funny. I was doing school certificate and we had a history exam. The question in the history exam was ‘describe the fall of Napoléon’. Well, the film didn’t deal with the fall of Napoléon, nor did any of my history lessons. And so I said: “It is impossible to understand the fall of Napoléon without knowing about the rise” and then I told the entire story of the film. (laugh) which must have startled the examiner. It probably entertained him but he failed me (laugh) having not answered the question.

Maurice Tourneur is one of your favourite directors. Which of his films impressed you particularly ?

Maurice Tourneur is one of your favourite directors. Which of his films impressed you particularly ?

The film that hooked me to Maurice Tourneur I had never seen. I read a programme note by William K. Everson and it was so beautifully written, it was so atmospheric, it talked about the film called Lorna Doone (1922) And I fell in love with that picture just from the programme note. Then I bought it, looked at it and was terribly disappointed. Terribly disappointed! And it was because it was a rotten dupe that had been made by some collector. And when I saw an original print with tints and tones and everything, it shot up in my estimation. But it still isn’t the film that it should be. It is an extraordinarily beautiful one. And the next thing that happened was very amusing. I had found a collection in the North, in the Lake District. And I examined the title frame of one of them and it said The Wishing Ring, an Idyll of Old England (1914). So I put it back because I thought it was a British silent film and I knew it would be disappointing. Then I told a friend who was doing a catalogue of English films about this and he looked it up, came back and said: “That’s not English, that’s American by Maurice Tourneur”. So I was most embarrassed. Luckily, the man hadn’t sold it. And I bought it for a pound a reel. And it turned out to be the most enchanting comedy, absolutely enchanting made as early as 1914. It was exquisite. So I was falling back in love with Maurice Tourneur again. And I began to see things like Trilby. But the one that really knocked me out was called Alias Jimmy Valentine made in 1915 and it obviously had a great impact on Fritz Lang because the opening of Die Spinnen (1919-20) has a sequence of a raid on an office shot exactly like Tourneur did above an open-plan office so you can see the routes of the criminals, and I saw in other Fritz Lang films reproduction of Tourneur scenes. Fascinating! Anyway…When I went to America, I met Tourneur’s art director Ben Carré, a Frenchman who had done films at Gaumont like La course aux potirons (The Pumpkin Race, 1907) he made all the pumpkins for them, he was the scenic designer and became Tourneur’s art director. And, then I started seeing things like The Blue Bird (1918). Some of the later ones were surprisingly bland and I realised that he had been a victim of exhibitor’s demanding the usual trash and he got so bored with fighting them that he gave in, and gave them what they wanted. That’s a bit disappointing. He never really delivered the masterpiece that he ought to have done. He made so many pictures that have disappeared. But he trained a young man called Clarence Brown and Clarence Brown–he had been an automobile engineer before he joined Tourneur- He had never been in the picture business at all. But he admired Tourneur films so much that he went out and sought him out and virtually demanded the job. He has the spirit in his silent films; he has everything of Tourneur plus good solid dramatic structure. I wanted to do a documentary about that school, that strange school of this Frenchman who arrived in America and creates an even better director than he was. At least, in that period.

The film that hooked me to Maurice Tourneur I had never seen. I read a programme note by William K. Everson and it was so beautifully written, it was so atmospheric, it talked about the film called Lorna Doone (1922) And I fell in love with that picture just from the programme note. Then I bought it, looked at it and was terribly disappointed. Terribly disappointed! And it was because it was a rotten dupe that had been made by some collector. And when I saw an original print with tints and tones and everything, it shot up in my estimation. But it still isn’t the film that it should be. It is an extraordinarily beautiful one. And the next thing that happened was very amusing. I had found a collection in the North, in the Lake District. And I examined the title frame of one of them and it said The Wishing Ring, an Idyll of Old England (1914). So I put it back because I thought it was a British silent film and I knew it would be disappointing. Then I told a friend who was doing a catalogue of English films about this and he looked it up, came back and said: “That’s not English, that’s American by Maurice Tourneur”. So I was most embarrassed. Luckily, the man hadn’t sold it. And I bought it for a pound a reel. And it turned out to be the most enchanting comedy, absolutely enchanting made as early as 1914. It was exquisite. So I was falling back in love with Maurice Tourneur again. And I began to see things like Trilby. But the one that really knocked me out was called Alias Jimmy Valentine made in 1915 and it obviously had a great impact on Fritz Lang because the opening of Die Spinnen (1919-20) has a sequence of a raid on an office shot exactly like Tourneur did above an open-plan office so you can see the routes of the criminals, and I saw in other Fritz Lang films reproduction of Tourneur scenes. Fascinating! Anyway…When I went to America, I met Tourneur’s art director Ben Carré, a Frenchman who had done films at Gaumont like La course aux potirons (The Pumpkin Race, 1907) he made all the pumpkins for them, he was the scenic designer and became Tourneur’s art director. And, then I started seeing things like The Blue Bird (1918). Some of the later ones were surprisingly bland and I realised that he had been a victim of exhibitor’s demanding the usual trash and he got so bored with fighting them that he gave in, and gave them what they wanted. That’s a bit disappointing. He never really delivered the masterpiece that he ought to have done. He made so many pictures that have disappeared. But he trained a young man called Clarence Brown and Clarence Brown–he had been an automobile engineer before he joined Tourneur- He had never been in the picture business at all. But he admired Tourneur films so much that he went out and sought him out and virtually demanded the job. He has the spirit in his silent films; he has everything of Tourneur plus good solid dramatic structure. I wanted to do a documentary about that school, that strange school of this Frenchman who arrived in America and creates an even better director than he was. At least, in that period.I think it’s underrated – the French influence on American cinema. Maurice Tourneur was just one director who was sent out to make picture of a higher standard than the American could do. Really to teach the Americans how to do it. But there was a cameraman Lucien Andriot, there was the art director Ben Carré, another director Emile Chautard, it’s a fascinating group who was brought out by Jules Brulatour who was the man who had the franchise for Eastman Kodak. Every time a handle was turned on a silent film camera, he made about a dollar! (laugh) So he was unbelievably wealthy. But he did us a favour by hiring those marvellous people like Albert Capellani! The only one I was really disappointed in was Louis Gasnier, his pictures are just so trashy! But that French group were tremendously important I think in bringing high standards to American pictures.

When I was in Hollywood, I managed to interview a lot of the people who worked for Tourneur: Charles Van Enger, the cameraman, Ben Carré, Jacques Tourneur, his son. I came to Paris and met Louise Lagrange with whom he lived the last 30 years of his life. I had shown The Wishing Ring at the NFT in 1960 and sent a rave letter to Tourneur just before he died. So I wrote a book about him using all this material. I never published it because I met Jacques Deslandes and he said he was writing a book about Maurice Tourneur. And when he showed me the documents that he had found, I admitted defeat immediately. He even had his exercise books from the Lycée Condorcet. Unbelievable! Scripts and contracts and letters…he disappeared! Nothing was heard from Jacques Deslandes. The documents disappeared. Fade out-Fade in. Many years later, two men from France came to see me at my office. They said they were writing a book about Maurice Tourneur. And they had the most amazing documents. They didn’t have the exercise books but they had the equivalent, really astonishing things! They disappeared too! (laugh) The documents have disappeared. I just don’t know what’s going on. So I appeal to anyone who is reading this and who has a lead on what happened to these precious documents. Somebody should do a book on Maurice Tourneur!

What is the main difference for you between French and American silents? Is it the cinematography, the narrative or the use of locations?

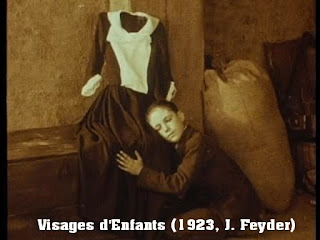

Well, recently I did a series of shows in Ireland and I showed them the best films I could think of in their categories; one was The Eagle (1926) which is a delightful light-hearted romantic picture with Valentino and Vilma Banky directed by Clarence Brown; Stella Dallas (1925) which is one the most emotional film you can ever hope to see directed by Henry King and then I showed Visages d’Enfants (Faces of Children, 1923-25). And that’s the one that got the audience. I was really surprised but I’ve always thought it was a great picture. And it is due to the fact there is an integrity about those films. Not that there isn’t about the American ones but there is a commercial imperative to an awful lot of American pictures which the French don’t bother with. And the best French films have a tremendous enthusiasm, integrity, love of cinema, beauty and that essential reality brought about by the use of locations. There is no compromise in the best of them which tends to be in American pictures. But there are also an awful lot of bad French films as you know! Nobody sets out to make a bad picture but money has an awful lot to do with it. The Americans used to do a terrible thing called the Poverty Row programme pictures, in which they would get a star for one day, they only had paid it for a day, take all the close-ups they could think of then sprinkle them throughout the picture…pathetic actually! There is no production value, no dramatic value, nothing…And they used to crank them faster in order to fill the 6 reels quicker. They are so cynical and there are too many of those, they’re just unbearable. They all survived because nobody ever wanted them back! Now the French didn’t do that. But they were forced to make pictures with very low budgets. And you just can’t expect quality when you’ve just no time and no money to make the picture with.

Well, recently I did a series of shows in Ireland and I showed them the best films I could think of in their categories; one was The Eagle (1926) which is a delightful light-hearted romantic picture with Valentino and Vilma Banky directed by Clarence Brown; Stella Dallas (1925) which is one the most emotional film you can ever hope to see directed by Henry King and then I showed Visages d’Enfants (Faces of Children, 1923-25). And that’s the one that got the audience. I was really surprised but I’ve always thought it was a great picture. And it is due to the fact there is an integrity about those films. Not that there isn’t about the American ones but there is a commercial imperative to an awful lot of American pictures which the French don’t bother with. And the best French films have a tremendous enthusiasm, integrity, love of cinema, beauty and that essential reality brought about by the use of locations. There is no compromise in the best of them which tends to be in American pictures. But there are also an awful lot of bad French films as you know! Nobody sets out to make a bad picture but money has an awful lot to do with it. The Americans used to do a terrible thing called the Poverty Row programme pictures, in which they would get a star for one day, they only had paid it for a day, take all the close-ups they could think of then sprinkle them throughout the picture…pathetic actually! There is no production value, no dramatic value, nothing…And they used to crank them faster in order to fill the 6 reels quicker. They are so cynical and there are too many of those, they’re just unbearable. They all survived because nobody ever wanted them back! Now the French didn’t do that. But they were forced to make pictures with very low budgets. And you just can’t expect quality when you’ve just no time and no money to make the picture with.The French have a reputation for the Avant-Garde and you keep seeing films like The Seashell and the Clergyman (la coquille et le clergyman, 1928, Germaine Dulac). But the great thing about French cinema is when the Avant-Garde is in the mainstream: i.e. Napoléon, L’argent, Michel Strogoff. Thrilling!

Which French directors did you actually meet in person?

In 1966, I went over to represent It Happened Here, paid for by UA, and I was given a publicity fellow called Bernard Eisenschitz. We both became great friends which we still are and he was fascinated by silent film history too and he took me around these old directors. I spent several days at UA expenses going round. One of them that we met was Viatcheslav Tourjansky who made Michel Strogoff. Now, Tourjansky happened to in Berlin in September 1939 and he worked for the Nazis. He was called Victor Tourjansky. And when I knocked on his door, it took him a full 5 minutes opening locks one after the other, before we could get in! And that’s obviously because he suspected the Resistance would track him down. (laugh) He was very cold; it was difficult to get him worked up about this. It was great shame but it was a fascinating experience to meet him. And he told me he’d gone to America because Michel Strogoff had been a great hit released by Universal. And funnily enough, he was hired by MGM to make The Cossacks (1928) and the cossacks came over with him. And there is a shot of them riding down the main street of Los Angeles. And then he was dropped from The Cossacks and George Hill took over and then Clarence Brown took over. And he ended up directing Tim McCoy’s westerns. So he decided to go back to France. But I hope I got it over to him what a wonderful film Michel Strogoff was. How much it had impressed me. That has an extraordinary sequence at the beginning where you see the rebellious Tartars in Siberia intercut with the dancers in the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. Absolutely superb editing, superb everything!

During the 20s, a company run by Russian émigrés, Albatros, was one of the main production companies in France. What do you think was their main contribution to French cinema?

That’s an interesting question. I would say Un chapeau de paille d’Italie (1927, René Clair) and Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1929, Jacques Feyder) and those films made by Russian emigres. I deeply regret that I could have gone to see Alexandre Kamenka [the head of the Albatros Studios] and didn’t. Liam O’Leary kept telling me about him, but I didn’t. But my interest in Russia started by seeing films like Michel Strogoff [It’s a Ciné France Film production.]

That’s an interesting question. I would say Un chapeau de paille d’Italie (1927, René Clair) and Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1929, Jacques Feyder) and those films made by Russian emigres. I deeply regret that I could have gone to see Alexandre Kamenka [the head of the Albatros Studios] and didn’t. Liam O’Leary kept telling me about him, but I didn’t. But my interest in Russia started by seeing films like Michel Strogoff [It’s a Ciné France Film production.]La Maison du Mystère (1922, A. Volkoff) I saw the whole of that, day after day at Pordenone, 10 episodes of it. Absolutely superb, le Brasier Ardent (1923, I. Mosjoukine). Oh and Mosjoukine! That’s their greatest contribution to the world. Mosjoukine is an absolutely unforgettable actor. Napoléon if it hadn’t been for Gance and Dieudonné, It was practically a Russian film. Actually nearly all the people who worked on it were Russians which is ironic when you consider what Napoléon was trying to do to Russia! (laugh) And I finally saw the original version of Le Lion des Mogols, it wasn’t nearly as bad as I thought it was in 9.5 mm 1 reel cut-down. I wonder if Souris d’hôtel (1927), the film has been preserved. I’ve always been fascinated by that, it’s directed by a fellow from Chile, Adelqui Millar who appears in British pictures a lot. It’s the most curious film, I hope they bring that out on DVD. But I bet they won’t.

Jacques de Baroncelli is forgotten name in France apart for a few talking pictures. Which of his silent films do you like particularly?

The two that I absolutely worship are Pêcheur d’Islande (1924) and Nêne (1923). I wasn’t particularly interested in La femme et le pantin (1929) which seems to have been made again and again, in America, here and in France. But Pêcheur d’Islande is particularly outstanding, heartbreaking picture and Nêne (1923) had that same quality. Mind you, Sandra Milowanoff again the Albatros actress from Russia, gives a great deal to these pictures and to Fescourt’s Les Misérables (1925). She is absolutely fabulous in that. That’s another magnificent film. I sat through all 7 hours of that in one sitting. Terrific! (laugh)

The two that I absolutely worship are Pêcheur d’Islande (1924) and Nêne (1923). I wasn’t particularly interested in La femme et le pantin (1929) which seems to have been made again and again, in America, here and in France. But Pêcheur d’Islande is particularly outstanding, heartbreaking picture and Nêne (1923) had that same quality. Mind you, Sandra Milowanoff again the Albatros actress from Russia, gives a great deal to these pictures and to Fescourt’s Les Misérables (1925). She is absolutely fabulous in that. That’s another magnificent film. I sat through all 7 hours of that in one sitting. Terrific! (laugh)You restored The Chess Player by Raymond Bernard with its original score by Henri Rabaud conducted by Carl Davis. How did you discover it?

I was hoping you were going to ask me about the restoration of that film because it’s such an extraordinary story. I bought Le Joueur d’Echecs on 9.5 mm in two reels. I think got a 4 reels version for the French which some reasons are completely different versions on 9.5 in France as they did in England. That completely satisfied my desire to make epics. To see this cavalery charge across my bedroom wall was thrilling. And funnily enough, it had an impact on Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) which I’ll tell about you later on. Lenny Borger worked for Variety and he rang me up and told me he was coming to London and I would like to see some French silents. I put the projector up and I ran him a series of pictures including Le Joueur d’Echecs. And he said: “Where is the original 35mm of that?” I said: “It doesn’t exist as far as I know. This is all there is.” Well, he didn’t accept that and he went looking for the 35mm. And one freezing December, he rang me from East Berlin and he told me he’d found it. “It’s in the DDR Archive. It’s not just a print. It’s the original camera negative.” So a charming man who ran the archive said he was perfectly happy for us to do something with this. And when I worked for Thames Television, it became possible. Now, it was missing Reel 1 and that was a bit of a disaster. So I then found a Dutch collector who had another print and it had a reel 1, but then we looked at it and it had been ruined by water damage. The irony is, the reason was this Bernard was in the East Berlin archive was that Tristan Bernard was Jewish. Raymond Bernard, Tristan and his wife were arrested by the French police, handed over to the Germans and shipped out to a concentration camp. At which point I think the Vichy government thought this is going too far. It’s like taking Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh out to a concentration camp. So they said: “bring them back”. So they returned them dutifully. But they had also seized the films. And that’s how they got hold of Le Joueur d’Echecs. So we salute the Gestapo who did a very good job at preservation! (laugh) except that they lost reel one. Finally Fred Junck in Luxembourg came up with a pristine reel 1. So David Gill and I were able to propose it to Thames Television and to Jeremy Isaacs. And we got Carl Davis to write the music. He began writing the music and ironically, a TV programme was made about him writing the music for Le Joueur d’Echecs. He then came across the Henri Rabaud score and said: “This is so good. We’ve got to use this!” And he scrapped what he had written. My God! He was right the Rabaud score was absolutely terrific. Now comes the moment when we are going to show it: 1990 at the Dominion, Tottenham Court Road. It was in December, dreadful night; snow everywhere, motorway cut off, projectionist at the other end of the motorway. My God! How are we going to show the film tonight? We get in a projectionist from the NFT who doesn’t know how to operate Victoria-8s which is what they had in the Dominion. The film starts, there is an image on the screen but it’s so dim, it looks as if there is a candle in the lamp house. There is more light blazing off the orchestra’s music stands than there is on the screen. I am in agony. I am walking up and down the projection box looking down... My God! After 40 min, the door bursts open and in comes the projectionist, looks through the port and says: “Oh My God!” Goes “Swish! Click!” and it looks perfect. And for the rest of the film, it’s perfect. Everybody comes out, I meet my friends and I say: “I am so sorry about that disaster.” They say: “What disaster?” They hadn’t even noticed…

Before the film was shown it had to arrive from East Germany, it was sent to Thames Television. There wasn’t a name on it, just Thames Television and the dispatch department didn’t know what to do with it. It said The Chess Players. So they looked it up and sure enough it was distributed by Connoisseur, it was a film made by Satyajit Ray with Richard Attenborough and they send it off to Austria. They thought they had a German language version of The Chess Players. It took an awful lot of persuasion to send it back! (laugh)

For The Charge of the Light Brigade, Tony Richardson had shot the battle scenes in Turkey and he lined up a lot of cannons and fired them. And they just seemed to squirt smoke. Now in Le Joueur d’Echecs, when the cannons go off, they leap backwards as they do when you’ve got live cannon balls in them. So I showed it to Tony and I said: “The cannons have got to look like this otherwise if I cut the charge, it’s going to seem very limp.” By God, he got the cannon back on Chobham Common, he got hydraulic mechanical systems operated by an American who happened to have been the son of the man who worked on the original Ben Hur -very helpful!- and we reshot it all on Chobham Common. So thank you, Raymond Bernard! (laugh)

Which forgotten French silent should get a DVD release immediately in your opinion?

Which forgotten French silent should get a DVD release immediately in your opinion?

Apart from Pêcheur d’Islande, I would like Thérèse Raquin (1928, J. Feyder)! (laugh) [the film is lost]. Michel Strogoff (1926, Viatcheslav Tourjansky) would be a wonderful one to do. Casanova (1927, Alexandre Volkoff) would be also a great idea; La Maison du Mystère (1922) by Alexandre Volkoff too. Oh! and Napoléon! (laugh)

Before the film was shown it had to arrive from East Germany, it was sent to Thames Television. There wasn’t a name on it, just Thames Television and the dispatch department didn’t know what to do with it. It said The Chess Players. So they looked it up and sure enough it was distributed by Connoisseur, it was a film made by Satyajit Ray with Richard Attenborough and they send it off to Austria. They thought they had a German language version of The Chess Players. It took an awful lot of persuasion to send it back! (laugh)

For The Charge of the Light Brigade, Tony Richardson had shot the battle scenes in Turkey and he lined up a lot of cannons and fired them. And they just seemed to squirt smoke. Now in Le Joueur d’Echecs, when the cannons go off, they leap backwards as they do when you’ve got live cannon balls in them. So I showed it to Tony and I said: “The cannons have got to look like this otherwise if I cut the charge, it’s going to seem very limp.” By God, he got the cannon back on Chobham Common, he got hydraulic mechanical systems operated by an American who happened to have been the son of the man who worked on the original Ben Hur -very helpful!- and we reshot it all on Chobham Common. So thank you, Raymond Bernard! (laugh)

Which forgotten French silent should get a DVD release immediately in your opinion?

Which forgotten French silent should get a DVD release immediately in your opinion?Apart from Pêcheur d’Islande, I would like Thérèse Raquin (1928, J. Feyder)! (laugh) [the film is lost]. Michel Strogoff (1926, Viatcheslav Tourjansky) would be a wonderful one to do. Casanova (1927, Alexandre Volkoff) would be also a great idea; La Maison du Mystère (1922) by Alexandre Volkoff too. Oh! and Napoléon! (laugh)

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire