Part 4

The Parade’s Gone By... and Hollywood

The Parade’s Gone By... and Hollywood

Kevin Brownlow recalls the shooting of the series Hollywood with a host of marvellous anecdotes about the great film-makers and actors he met.

Lisez la traduction française et écoutez les extraits sonores ici.

You told me how difficult it had been to find a publisher for The Parade’s Gone By... in the 60s. What was the status of silent pictures at that time?

I remember that the attitude of the middle-aged person (some of whom went back that far): “Oh you don’t want to bother about those! They were ludicrously acted, badly photographed, speeded up”…That was the general feeling, there was a really strong attitude against them. Talkies were such a fantastic advance and these were just ludicrous antiques, embarrassing to see now. That was the general feeling. And I went to people’s home, sat them down, put my projector up and always got a terrific thrill out of the way they reacted. They were quite astonished by… “It looks SO MODERN!” Is modern such a compliment?

How easy was it to meet all those directors, actors and technicians? Were they happy to discuss their silent work?

Yes, first of all they were the most extraordinary people I have ever met in my life. They were only a couple of Sunset Boulevard type characters. But those of course are always the colourful ones that ones talks about. What astonished me was how articulate they were, how eloquent they were, how enthusiastic they still were, but how they had been convinced by this black propaganda that silent films were pathetic. So they had no real pride in their work. Again, it was very exciting to meet someone like Reginald Denny, sit him and his family down, show him one of his Universal comedies. And he had no idea they were as good as that. Absolutely no idea.

What was your initial reaction when you were offered to direct a TV series on silent picture?

To run in the opposite direction. I had no interest in TV. I had a very snobbish attitude towards TV. I was a film maker with a capital F and a capital M. And it was my wife who forced me to do it. I just thought it would be like an alcoholic’s cure to go along to a TV company and they would just wreck it and wouldn’t give it enough time, enough money and enough care. And, in fact, exactly the opposite! David Gill turned out to be more rigorous than I was. Just astonishing how much money they spent. They spent a million back in the 70s on that all series. There was no feeling that they were holding back. For instance, they were some difficulties about, for instance, Lillian Gish.

We couldn’t get Lillian Gish to do an interview and finally her manager said: “she’s done her own programme. You’ll have to buy that first.” They did! They spent a lot of money and bought this thing which they showed at one o’clock in the afternoon or something. And then they also paid her substantially. So I cannot say that they didn’t do their damnest to do that series work. The only drawback was that their American distributor sold the series piecemeal. The TV stations had no interest in the series and when the comedy episode went out in LA, they cut Buster Keaton out because a basket ball match was overrunning. And we were told we’d been treated like chopped liver. Now, that had serious consequences because Thames sent David and me out to survey the ground for making a second series on the 30s. And because it had been so badly distributed… It should have been sold to PBS and shown across the nation in one great sweep. We contacted James Stewart and Fred Astaire, all those people, and they’d never heard of the series. What series? So we had nothing to build on and it was never made.

We couldn’t get Lillian Gish to do an interview and finally her manager said: “she’s done her own programme. You’ll have to buy that first.” They did! They spent a lot of money and bought this thing which they showed at one o’clock in the afternoon or something. And then they also paid her substantially. So I cannot say that they didn’t do their damnest to do that series work. The only drawback was that their American distributor sold the series piecemeal. The TV stations had no interest in the series and when the comedy episode went out in LA, they cut Buster Keaton out because a basket ball match was overrunning. And we were told we’d been treated like chopped liver. Now, that had serious consequences because Thames sent David and me out to survey the ground for making a second series on the 30s. And because it had been so badly distributed… It should have been sold to PBS and shown across the nation in one great sweep. We contacted James Stewart and Fred Astaire, all those people, and they’d never heard of the series. What series? So we had nothing to build on and it was never made.

How long did it take you to make the 13-episodes Hollywood series with David Gill?

It took 4 years. Can you believe that? For a long time, nothing seemed to be happening at all because the studios ran by the people we’ve been discussing, wouldn’t let us have a frame. And MGM had made That’s Entertainment (1974) and they suddenly realised their vaults were gold mines and “No, we’re not letting anything out on TV.” Then, they made That’s Entertainment II: big flop! Suddenly, the vaults opened up, albeit at great expense. But Thames paid it and we got everything, practically everything we wanted. Even the difficult people, like Goldwyn, they sorted them out and we got The Winning of Barbara Worth (1926, H. King) which I never thought we would get.

You got the opportunity to meet a staggering number of great American directors. Could you tell us something about King Vidor: what kind of a person was he?

Hmmm… Let me tell you another story talking of directors. I was at the Masquer’s club at Hollywood being stood up by the Duncan Sisters and I was waiting and waiting for this… I didn’t particularly want to meet them but they were on in the silent days, they were on the list and a woman said… She saw me looking at a photograph and she said: “Who’s that?” “That’s Fred Niblo.” “Oh yes! Well, you shouldn’t know that!” I said: “I am very interested in silent films and directors;” She said: “Oh! I’m married to one.” I said: “Who?” “Oh, no one you’ve ever heard of: Joseph Henabery.” “Oh my God! Abraham Lincoln in The Birth of a Nation (1915, D.W. Griffith)!” She said: “You’ve heard of him?” (laugh) So she fixed a meeting! I went around to meet Joseph Henabery and there was this tall, very dignified character of whom Bessie Love said had the outlook of Abraham Lincoln. And he was so interesting and so charming. And we had the most fantastic time and I recorded four hours of tape on the first trip. And sometimes, someone like him would recommend another person. But most of the time I had to ring them up, explain who I was and King Vidor I had met way back in the early 60s because Al Parker had told me he was in town. And so he was the first that I went to see after Parker. And he was so easy to talk to, so charming and so fascinating. I got to know him very well. He invited me and my wife to his ranch in Paso Robles and showed us films in the evening and we did the interviews during the day. He took us around the ranch, the streets of which were called Sunset Boulevard, Vine Street… (laugh) He always wore a Stetson. He was a dream to interview. He seemed so youthful.

The directors I suppose were my pets. I remember Raoul Walsh, meeting him in one of those American restaurants that’s terribly dark. They keep them like that for ladies of a certain age. And he was looking at the menu; his Stetson was on the seat, he had cowboy boots, his eye patch. And he was looking at the menu like this. I remember him saying: “Jesus Christ! A guy could go blind in here ordering ham and eggs!” (laugh) They all had the most marvellous way of talking.

The directors I suppose were my pets. I remember Raoul Walsh, meeting him in one of those American restaurants that’s terribly dark. They keep them like that for ladies of a certain age. And he was looking at the menu; his Stetson was on the seat, he had cowboy boots, his eye patch. And he was looking at the menu like this. I remember him saying: “Jesus Christ! A guy could go blind in here ordering ham and eggs!” (laugh) They all had the most marvellous way of talking.

Byron Haskin is a typical example. If you ask an Englishman, how hot were the lights on the set? They’d say: “Oh! Very hot.” Well it’s informative, you know where you are. But these fellows had the Irish way of talking. And Byron Haskin said: “Hot!!! Jesus! You could light a cigar on a beam at a hundred yards!” (laugh) Fabulous!

William Wellman appears like an extremely energetic character when he describes the shooting of Wings. Did he really deserve his nickname ‘Wild Bill’?

Oh yes! He was really something in his youth. He was a juvenile delinquent. And he said: “The trouble was my probation officer was my mother.” (laugh) He would pinch cars and go for joy rides. That’s the reason why he went to the Lafayette Flying Corps, a way to get rid of him! He was again absolutely like somebody out of the old west. I don’t think he told the truth. Howard Hawks was the most difficult one. Nonetheless Wellman was mesmerizing.

I’m trying to think of the ones that were really difficult. There was one called Nick Grinde who made B pictures and he just played with me when I was trying to interview him and wouldn’t answer properly. But the rest of them were so enthusiastic, and obviously still in love with the movies…and another one we liked very much was Edward Sloman. But when I first interviewed him and asked about his films, he’d say: “Oh yes! I EARNED 17,000 $ a week on that one!” (laugh) and then you asked him about this other film and “25,000 $ a week!!!” (laugh)

Henry King is also featured prominently in your series.

I remember that the attitude of the middle-aged person (some of whom went back that far): “Oh you don’t want to bother about those! They were ludicrously acted, badly photographed, speeded up”…That was the general feeling, there was a really strong attitude against them. Talkies were such a fantastic advance and these were just ludicrous antiques, embarrassing to see now. That was the general feeling. And I went to people’s home, sat them down, put my projector up and always got a terrific thrill out of the way they reacted. They were quite astonished by… “It looks SO MODERN!” Is modern such a compliment?

How easy was it to meet all those directors, actors and technicians? Were they happy to discuss their silent work?

Yes, first of all they were the most extraordinary people I have ever met in my life. They were only a couple of Sunset Boulevard type characters. But those of course are always the colourful ones that ones talks about. What astonished me was how articulate they were, how eloquent they were, how enthusiastic they still were, but how they had been convinced by this black propaganda that silent films were pathetic. So they had no real pride in their work. Again, it was very exciting to meet someone like Reginald Denny, sit him and his family down, show him one of his Universal comedies. And he had no idea they were as good as that. Absolutely no idea.

What was your initial reaction when you were offered to direct a TV series on silent picture?

To run in the opposite direction. I had no interest in TV. I had a very snobbish attitude towards TV. I was a film maker with a capital F and a capital M. And it was my wife who forced me to do it. I just thought it would be like an alcoholic’s cure to go along to a TV company and they would just wreck it and wouldn’t give it enough time, enough money and enough care. And, in fact, exactly the opposite! David Gill turned out to be more rigorous than I was. Just astonishing how much money they spent. They spent a million back in the 70s on that all series. There was no feeling that they were holding back. For instance, they were some difficulties about, for instance, Lillian Gish.

We couldn’t get Lillian Gish to do an interview and finally her manager said: “she’s done her own programme. You’ll have to buy that first.” They did! They spent a lot of money and bought this thing which they showed at one o’clock in the afternoon or something. And then they also paid her substantially. So I cannot say that they didn’t do their damnest to do that series work. The only drawback was that their American distributor sold the series piecemeal. The TV stations had no interest in the series and when the comedy episode went out in LA, they cut Buster Keaton out because a basket ball match was overrunning. And we were told we’d been treated like chopped liver. Now, that had serious consequences because Thames sent David and me out to survey the ground for making a second series on the 30s. And because it had been so badly distributed… It should have been sold to PBS and shown across the nation in one great sweep. We contacted James Stewart and Fred Astaire, all those people, and they’d never heard of the series. What series? So we had nothing to build on and it was never made.

We couldn’t get Lillian Gish to do an interview and finally her manager said: “she’s done her own programme. You’ll have to buy that first.” They did! They spent a lot of money and bought this thing which they showed at one o’clock in the afternoon or something. And then they also paid her substantially. So I cannot say that they didn’t do their damnest to do that series work. The only drawback was that their American distributor sold the series piecemeal. The TV stations had no interest in the series and when the comedy episode went out in LA, they cut Buster Keaton out because a basket ball match was overrunning. And we were told we’d been treated like chopped liver. Now, that had serious consequences because Thames sent David and me out to survey the ground for making a second series on the 30s. And because it had been so badly distributed… It should have been sold to PBS and shown across the nation in one great sweep. We contacted James Stewart and Fred Astaire, all those people, and they’d never heard of the series. What series? So we had nothing to build on and it was never made.How long did it take you to make the 13-episodes Hollywood series with David Gill?

It took 4 years. Can you believe that? For a long time, nothing seemed to be happening at all because the studios ran by the people we’ve been discussing, wouldn’t let us have a frame. And MGM had made That’s Entertainment (1974) and they suddenly realised their vaults were gold mines and “No, we’re not letting anything out on TV.” Then, they made That’s Entertainment II: big flop! Suddenly, the vaults opened up, albeit at great expense. But Thames paid it and we got everything, practically everything we wanted. Even the difficult people, like Goldwyn, they sorted them out and we got The Winning of Barbara Worth (1926, H. King) which I never thought we would get.

You got the opportunity to meet a staggering number of great American directors. Could you tell us something about King Vidor: what kind of a person was he?

Hmmm… Let me tell you another story talking of directors. I was at the Masquer’s club at Hollywood being stood up by the Duncan Sisters and I was waiting and waiting for this… I didn’t particularly want to meet them but they were on in the silent days, they were on the list and a woman said… She saw me looking at a photograph and she said: “Who’s that?” “That’s Fred Niblo.” “Oh yes! Well, you shouldn’t know that!” I said: “I am very interested in silent films and directors;” She said: “Oh! I’m married to one.” I said: “Who?” “Oh, no one you’ve ever heard of: Joseph Henabery.” “Oh my God! Abraham Lincoln in The Birth of a Nation (1915, D.W. Griffith)!” She said: “You’ve heard of him?” (laugh) So she fixed a meeting! I went around to meet Joseph Henabery and there was this tall, very dignified character of whom Bessie Love said had the outlook of Abraham Lincoln. And he was so interesting and so charming. And we had the most fantastic time and I recorded four hours of tape on the first trip. And sometimes, someone like him would recommend another person. But most of the time I had to ring them up, explain who I was and King Vidor I had met way back in the early 60s because Al Parker had told me he was in town. And so he was the first that I went to see after Parker. And he was so easy to talk to, so charming and so fascinating. I got to know him very well. He invited me and my wife to his ranch in Paso Robles and showed us films in the evening and we did the interviews during the day. He took us around the ranch, the streets of which were called Sunset Boulevard, Vine Street… (laugh) He always wore a Stetson. He was a dream to interview. He seemed so youthful.

The directors I suppose were my pets. I remember Raoul Walsh, meeting him in one of those American restaurants that’s terribly dark. They keep them like that for ladies of a certain age. And he was looking at the menu; his Stetson was on the seat, he had cowboy boots, his eye patch. And he was looking at the menu like this. I remember him saying: “Jesus Christ! A guy could go blind in here ordering ham and eggs!” (laugh) They all had the most marvellous way of talking.

The directors I suppose were my pets. I remember Raoul Walsh, meeting him in one of those American restaurants that’s terribly dark. They keep them like that for ladies of a certain age. And he was looking at the menu; his Stetson was on the seat, he had cowboy boots, his eye patch. And he was looking at the menu like this. I remember him saying: “Jesus Christ! A guy could go blind in here ordering ham and eggs!” (laugh) They all had the most marvellous way of talking.Byron Haskin is a typical example. If you ask an Englishman, how hot were the lights on the set? They’d say: “Oh! Very hot.” Well it’s informative, you know where you are. But these fellows had the Irish way of talking. And Byron Haskin said: “Hot!!! Jesus! You could light a cigar on a beam at a hundred yards!” (laugh) Fabulous!

William Wellman appears like an extremely energetic character when he describes the shooting of Wings. Did he really deserve his nickname ‘Wild Bill’?

Oh yes! He was really something in his youth. He was a juvenile delinquent. And he said: “The trouble was my probation officer was my mother.” (laugh) He would pinch cars and go for joy rides. That’s the reason why he went to the Lafayette Flying Corps, a way to get rid of him! He was again absolutely like somebody out of the old west. I don’t think he told the truth. Howard Hawks was the most difficult one. Nonetheless Wellman was mesmerizing.

I’m trying to think of the ones that were really difficult. There was one called Nick Grinde who made B pictures and he just played with me when I was trying to interview him and wouldn’t answer properly. But the rest of them were so enthusiastic, and obviously still in love with the movies…and another one we liked very much was Edward Sloman. But when I first interviewed him and asked about his films, he’d say: “Oh yes! I EARNED 17,000 $ a week on that one!” (laugh) and then you asked him about this other film and “25,000 $ a week!!!” (laugh)

Henry King is also featured prominently in your series.

Oh my God! He was a biblical character. Very tall, very handsome, incredibly dignified with a charisma I cannot describe to you. When he was talking to you, you were lost in what he was saying. And we were so impressed that we can back and shot him again the following day, and again. And sent the rushes back and the word came through: adequate. Ok. Because charisma doesn’t transfer itself to celluloid which why of course people employ actors. He was an actor but as a man, he had fantastic charisma and it just doesn’t come across at all on the film. And that was a tremendous disappointment.

Oh my God! He was a biblical character. Very tall, very handsome, incredibly dignified with a charisma I cannot describe to you. When he was talking to you, you were lost in what he was saying. And we were so impressed that we can back and shot him again the following day, and again. And sent the rushes back and the word came through: adequate. Ok. Because charisma doesn’t transfer itself to celluloid which why of course people employ actors. He was an actor but as a man, he had fantastic charisma and it just doesn’t come across at all on the film. And that was a tremendous disappointment.The man the crew chose as the most impressive of all was a man confined to a wheelchair that’d had a severe stroke and could hardly talk. And that was Lewis Milestone.

Some people gave some very emotional testimonies in this series. I am thinking of Janet Gaynor as she recalls being directed by Murnau in Sunrise or Jackie Coogan describing the shooting of the most dramatic scene in The Kid. There is also John Wayne, his eyes misty with tears, recalling his late friend Harry Carey Sr. How did you manage to get such testimonies from them?

Yes! That’s very interesting!

Janet Gaynor was a naturally emotional person. She probably hadn’t talked about it for decades and suddenly she was talking about the most important moments in her life. And it was very moving just to sit there and hear all this amazing description of shooting one of these legendary films.

Now Jackie Coogan was a different matter. Jackie Coogan was delivering perfectly satisfactorily. I had not seen The Kid in a proper version. I had seen pirate prints. I had not been impressed. David had just seen the proper version of The Kid and had been tremendously impressed and he knew I wasn’t getting out of Jackie Coogan what I should be getting. So he kept stopping the camera, coming down and talking to Jackie more and more…and Coogan realised he was being reminded of the film. And David got that choked up reaction from him. Then I was back to London and saw The Kid and thought: “My God!” I saw what David had seen and was knocked out by The Kid. And I wished I’d seen that before. It would have made such difference. If you admire somebody tremendously, there is something unsaid in the way you talk to them. And that wasn’t happening in my case with Coogan.

Now Jackie Coogan was a different matter. Jackie Coogan was delivering perfectly satisfactorily. I had not seen The Kid in a proper version. I had seen pirate prints. I had not been impressed. David had just seen the proper version of The Kid and had been tremendously impressed and he knew I wasn’t getting out of Jackie Coogan what I should be getting. So he kept stopping the camera, coming down and talking to Jackie more and more…and Coogan realised he was being reminded of the film. And David got that choked up reaction from him. Then I was back to London and saw The Kid and thought: “My God!” I saw what David had seen and was knocked out by The Kid. And I wished I’d seen that before. It would have made such difference. If you admire somebody tremendously, there is something unsaid in the way you talk to them. And that wasn’t happening in my case with Coogan. Now, John Wayne was on a glass that size full of colourless liquid at 10 o’clock in the morning. And he started directing. He said: “I tell you what we do. See this bronze? We start down here and we move back up..” And the cameraman said: “ No, no, no, we don’t do anything like that!” (laugh) He was furious and walked out and I had to rush next door and plead with him to come back on the set. “Say! You know..” and his collar was turned up, he was fighting with it, when the camera was on him. Turn over; you could almost hear an orchestra start up. He was a different man. He was so charming and he not only told the story that you see in the film about The Searchers (1956, J. Ford), which had me choked up as well as he was telling it, but he told the most wonderfully funny stories about the making of The Big Trail (1930, R. Walsh). And he imitated Tyrone Power Sr. That was so funny. I wished we’d used it! But in the end, he was arm in arm with the cameraman. He looked at his bracelet and he said: “Ah! You’ve been in Vietnam!” (laugh) and they were on each other’s neck from that moment…(laugh)

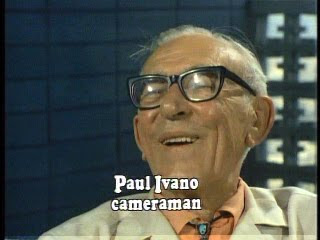

Now, John Wayne was on a glass that size full of colourless liquid at 10 o’clock in the morning. And he started directing. He said: “I tell you what we do. See this bronze? We start down here and we move back up..” And the cameraman said: “ No, no, no, we don’t do anything like that!” (laugh) He was furious and walked out and I had to rush next door and plead with him to come back on the set. “Say! You know..” and his collar was turned up, he was fighting with it, when the camera was on him. Turn over; you could almost hear an orchestra start up. He was a different man. He was so charming and he not only told the story that you see in the film about The Searchers (1956, J. Ford), which had me choked up as well as he was telling it, but he told the most wonderfully funny stories about the making of The Big Trail (1930, R. Walsh). And he imitated Tyrone Power Sr. That was so funny. I wished we’d used it! But in the end, he was arm in arm with the cameraman. He looked at his bracelet and he said: “Ah! You’ve been in Vietnam!” (laugh) and they were on each other’s neck from that moment…(laugh)Among the technicians featured in your series, there are quite a few cinematographers. I was particularly impressed by Karl Brown and Paul Ivano who gave some very interesting insights on working with D.W. Griffith and Erich von Stroheim. How did you find them?

When I was in the AFI, I received a message from the MoMA. Is Karl Brown still alive? And I replied: “No, if he was, I’d know!” because I’ve always wanted to meet him. Well, thank God, they didn’t take my word for it. They rang a fellow George J. Mitchell who was a military intelligence officer during the war and he did the obvious thing, he looked in the telephone book and there was a Karl Brown. He hadn’t had time to follow this up, so he rang me. It was a bit embarrassing; having said that the man isn’t alive and being told that he is! (laugh) OK I went over to that address and he’d left. The landlord said he’d gone with his wife and he had no idea where. So now began, I think it took 6 weeks, in which we did everything we could to find this man. We even stopped old men on the street and said: “You weren’t in the picture business, were you?” And they replied: “No, I was in Wall Street. I can tell you all about it!” “Yes, thanks very much!” (laugh) And it was an extraordinary period. We searched various bureaus downtown, the death certificates and everything else. And I can’t remember whom I was interviewing, but I was interviewing somebody. And the telephone kept ringing and I kept putting them off. It was actually somebody telling me that the department of motor vehicle had left a message and the message was Karl Brown’s address! So that night my wife and I got into her Volkswagen and we went along Laurel Canyon. It was very very misty and it was like going back in a H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. The trouble with LA, a road would go along and then it would be blocked off with lots and lots of buildings, and then starts again and it gets block off. It’s terribly difficult to find it. The numbers are endless, you know. We eventually found it and the bungalow was completely dark. I knocked on the door and nobody came. Anticlimax! I was just leaving when I saw an extraordinary thing. I saw a motion picture on the wall in colour. Then I saw the credits and credits were rolling backwards and I realised it was a picture on the wall, reflecting the television set, a colour TV set which was beneath the window. So I knocked and I rang. And eventually shuffle, shuffle, the oldest old woman you ever saw in your life came to the door. I said: “Does Karl Brown live here?” “How did you find us?” Shuffle, shuffle and then she came back and said: “He’ll see you!” And in I went, to another part of the house and there was Karl Brown, sitting in an armchair, as though he’d been waiting. And he just switched on like that as though he’d been interviewed everyday for a year. And he started talking about Griffith, The Birth of a Nation, Intolerance…Unbelievable! I kept going back and interviewing him some more. Every time it was gold dust! I finally persuaded him to write his book because I saw that he was a writer. And he did! He produced a fabulous book which was published as Adventures with D.W. Griffith. And then he went on and he wrote another one. But unfortunately the publisher of Adventures with D.W. Griffith got in touch with him separately and told him not to write more than 30,000 words. And for the first book, he’d written lots more. It was easy to take it out, but the information was saved. But in the second one, The Paramount Adventure, he just wrote what was required and so an awful lot has been lost. He also wrote one on Monogram. Anyway, he was one of the richest sources. And I came to him through a film I discovered at the Czech film archives in 1968 when Andrew and I went over, just after the Russian had invaded it. And Myrtle Frieda, the head of the archive showed us his favourite American silent which was Stark Love (1927) and I wrote an article about that. And that lead to the film being rescued by the MoMA. I think out of all the films that appeared in the Hollywood series, the one with the finest quality was The Covered Wagon (1923, James Cruze) photographed by Karl Brown in which we have many magnificently photographed films, but just for sheer guts, the image quality was stunning.

When I was in the AFI, I received a message from the MoMA. Is Karl Brown still alive? And I replied: “No, if he was, I’d know!” because I’ve always wanted to meet him. Well, thank God, they didn’t take my word for it. They rang a fellow George J. Mitchell who was a military intelligence officer during the war and he did the obvious thing, he looked in the telephone book and there was a Karl Brown. He hadn’t had time to follow this up, so he rang me. It was a bit embarrassing; having said that the man isn’t alive and being told that he is! (laugh) OK I went over to that address and he’d left. The landlord said he’d gone with his wife and he had no idea where. So now began, I think it took 6 weeks, in which we did everything we could to find this man. We even stopped old men on the street and said: “You weren’t in the picture business, were you?” And they replied: “No, I was in Wall Street. I can tell you all about it!” “Yes, thanks very much!” (laugh) And it was an extraordinary period. We searched various bureaus downtown, the death certificates and everything else. And I can’t remember whom I was interviewing, but I was interviewing somebody. And the telephone kept ringing and I kept putting them off. It was actually somebody telling me that the department of motor vehicle had left a message and the message was Karl Brown’s address! So that night my wife and I got into her Volkswagen and we went along Laurel Canyon. It was very very misty and it was like going back in a H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. The trouble with LA, a road would go along and then it would be blocked off with lots and lots of buildings, and then starts again and it gets block off. It’s terribly difficult to find it. The numbers are endless, you know. We eventually found it and the bungalow was completely dark. I knocked on the door and nobody came. Anticlimax! I was just leaving when I saw an extraordinary thing. I saw a motion picture on the wall in colour. Then I saw the credits and credits were rolling backwards and I realised it was a picture on the wall, reflecting the television set, a colour TV set which was beneath the window. So I knocked and I rang. And eventually shuffle, shuffle, the oldest old woman you ever saw in your life came to the door. I said: “Does Karl Brown live here?” “How did you find us?” Shuffle, shuffle and then she came back and said: “He’ll see you!” And in I went, to another part of the house and there was Karl Brown, sitting in an armchair, as though he’d been waiting. And he just switched on like that as though he’d been interviewed everyday for a year. And he started talking about Griffith, The Birth of a Nation, Intolerance…Unbelievable! I kept going back and interviewing him some more. Every time it was gold dust! I finally persuaded him to write his book because I saw that he was a writer. And he did! He produced a fabulous book which was published as Adventures with D.W. Griffith. And then he went on and he wrote another one. But unfortunately the publisher of Adventures with D.W. Griffith got in touch with him separately and told him not to write more than 30,000 words. And for the first book, he’d written lots more. It was easy to take it out, but the information was saved. But in the second one, The Paramount Adventure, he just wrote what was required and so an awful lot has been lost. He also wrote one on Monogram. Anyway, he was one of the richest sources. And I came to him through a film I discovered at the Czech film archives in 1968 when Andrew and I went over, just after the Russian had invaded it. And Myrtle Frieda, the head of the archive showed us his favourite American silent which was Stark Love (1927) and I wrote an article about that. And that lead to the film being rescued by the MoMA. I think out of all the films that appeared in the Hollywood series, the one with the finest quality was The Covered Wagon (1923, James Cruze) photographed by Karl Brown in which we have many magnificently photographed films, but just for sheer guts, the image quality was stunning. Paul Ivano must have been recommended by Robert Florey. He was a friend of Florey. He was quite surprising. He was a Serb and he served in the French Army during WWI. He was used as a technical adviser on The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921, R. Ingram) and he worked with most interesting characters but the most interesting was Erich von Stroheim and he told us with no sense of shame what went on that picture…(laugh) Our eyes were on stalks! I’ll tell you an odd thing. He lived with Valentino and Natacha in a sort of strange ménage à trois. And you remember this funny: “ahaha!” every time he would say something, he’d go “ahahaha!” and he said: “ahahaha! I haven’t seen him for quite a while.” He died in 1926, I think. I said: “What do you mean?” He said: “I saw him just recently. Ahaha!” “Who?” “Valentino! He appeared here!” “Oh!” (laugh) He was seeing Valentino…(laugh) very worrying…

Paul Ivano must have been recommended by Robert Florey. He was a friend of Florey. He was quite surprising. He was a Serb and he served in the French Army during WWI. He was used as a technical adviser on The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921, R. Ingram) and he worked with most interesting characters but the most interesting was Erich von Stroheim and he told us with no sense of shame what went on that picture…(laugh) Our eyes were on stalks! I’ll tell you an odd thing. He lived with Valentino and Natacha in a sort of strange ménage à trois. And you remember this funny: “ahaha!” every time he would say something, he’d go “ahahaha!” and he said: “ahahaha! I haven’t seen him for quite a while.” He died in 1926, I think. I said: “What do you mean?” He said: “I saw him just recently. Ahaha!” “Who?” “Valentino! He appeared here!” “Oh!” (laugh) He was seeing Valentino…(laugh) very worrying…I think you are very fond of cinematographer John F. Seitz. Nowadays, he is mostly remembered for his work with Billy Wilder on Sunset Boulevard and Double Indemnity. But, his silent career was also impressive with Rex Ingram’s Scaramouche and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. What innovations did he bring to cinematography?

Oh God! He changed the look of American pictures and he had a number of followers, Byron Haskin, a cameraman was one. And you can see in Don Juan and the Warner Brothers pictures that Haskin photographed, a tremendous debt to Ingram and Seitz. There is a lovely story in the Hollywood series about Seitz is his low-key lighting and the lab man would come along to look at his set, worrying about the thinness of the negative: “OK, you can switch the lights on now, John!” “They are on!” (laugh) He was strange man. He seemed very nervous and really shook up in his old age, but, he insisted on driving. And he drove up to the AFI, we had a long interview. And then went off again. And fade out. Fade in. In came an angry fellow from the AFI, he said: “Was that fellow in the Cadillac connected with you?” I said: “What? John Seitz? Yes, why?” He hit six cars going out of the estate and I had to pay for it! (laugh)

But what was marvellous was that John Seitz put me in touch with Alice Terry. She was a recluse really. But I rang her up, mentioned this reassuring name and that I was going to run The Conquering Power (1921, R. Ingram) and would she like to see it? I thought she’d refuse and she said: “Could I bring my sister?” (laugh) So they turned up, Alice Terry, her sister, the cameraman Seitz, the editor Grant Whytock, and several other people from the Ingram crowd. They all gathered and saw this fascinating film. And they all opened up and we were invited back to Alice’s place many many times. The only thing she wouldn’t do was to appear on the Hollywood programme. It was really upsetting because we really needed her. To think that she was there and wouldn’t do it. But she was concerned with the weight she’d put on.

Louise Brooks discusses her friend Clara Bow with enormous warmth though she never mentions her own work. Did she still despise Hollywood as a whole?

No she loved it. She was writing about it as much as she could. She was researching Wellman, and researching Mal St. Clair and she wrote a whole series of articles for Sight & Sound. First of all, how do we get her to do it? I knew she was going to be very very difficult. So we brought Bessie Love over. And when Louise heard that Bessie Love was with us, she agreed we could come on over. And so we flew up to Rochester and she was thrilled to meet Bessie Love. That put her in a great good humour and yes, she’d do it. So we set up and we got the cameraman and the sound recordist in this tiny apartment. And Louise was firing on all cylinders talking about Clara Bow. Because she was very angry that I hadn’t included Clara Bow in my book which was pure oversight because I was mad about Clara Bow. She’d done that part and we getting her on her own work and suddenly the sound recordist took off his earphones and said: “CUT! Sounds like a bathroom in here!” And that put her in such a bad temper that we couldn’t use the rest of the interview. She was growling it out. The sound recordist does not cut the scene! I could have killed him…

No she loved it. She was writing about it as much as she could. She was researching Wellman, and researching Mal St. Clair and she wrote a whole series of articles for Sight & Sound. First of all, how do we get her to do it? I knew she was going to be very very difficult. So we brought Bessie Love over. And when Louise heard that Bessie Love was with us, she agreed we could come on over. And so we flew up to Rochester and she was thrilled to meet Bessie Love. That put her in a great good humour and yes, she’d do it. So we set up and we got the cameraman and the sound recordist in this tiny apartment. And Louise was firing on all cylinders talking about Clara Bow. Because she was very angry that I hadn’t included Clara Bow in my book which was pure oversight because I was mad about Clara Bow. She’d done that part and we getting her on her own work and suddenly the sound recordist took off his earphones and said: “CUT! Sounds like a bathroom in here!” And that put her in such a bad temper that we couldn’t use the rest of the interview. She was growling it out. The sound recordist does not cut the scene! I could have killed him…Gloria Swanson still looked stunning when you filmed her. She comes through as a very strong personality. How was she as a person?

I knew Gloria Swanson from London. She was very difficult to get hold of. I was given her telephone number and I rang it. And I gave my usual pitch, how interested I was in her. “Do you mind?” How fascinated I was. “Do you mind?” (laugh) So I had to go through somebody else. And eventually I got to meet her and we got on like a house on fire. In fact, I was going to make a film for her, two films for her. I was going to make film about Queen Kelly for the BBC and that was blocked by the man who’d made I Claudius. He says: “If that film is made. I’ll direct it! You don’t.” And the other thing I was going to do was something about a religious woman she wanted a film made about. She tried to get me to do that.

I knew Gloria Swanson from London. She was very difficult to get hold of. I was given her telephone number and I rang it. And I gave my usual pitch, how interested I was in her. “Do you mind?” How fascinated I was. “Do you mind?” (laugh) So I had to go through somebody else. And eventually I got to meet her and we got on like a house on fire. In fact, I was going to make a film for her, two films for her. I was going to make film about Queen Kelly for the BBC and that was blocked by the man who’d made I Claudius. He says: “If that film is made. I’ll direct it! You don’t.” And the other thing I was going to do was something about a religious woman she wanted a film made about. She tried to get me to do that.She had a front which was the Great Star. If I said Norma Desmond I wouldn’t be far wrong. She was haughty, difficult to talk to, snobbish, all the things you didn’t want her to be. But it was just a front and once you’d gone through that, she was like a tomboy. She suddenly became very funny, really charming and terrific! So long as you could keep that first thing at bay. But then long gaps, in which she’d go back to that. It was very difficult getting that interview and we had to pay an awful lot of money. She was one of the last people to surrender. And I thought of every question I could possibly ask her. What I never realised was she would be on the same programme as Valentino. And I forgot to ask her about Beyond the Rocks (1922, S. Wood). And then I comforted myself by saying well Beyond the Rocks is a lost film. We should have covered it. We didn’t but nobody will know because the film will never be discovered. (laugh) And then of course, it was! Very unfortunate…

But it was a tremendous interview and there’s much more there than we used, obviously and she was suggesting that she wouldn’t be surprised if William Desmond Taylor was not shot by orders of Paramount Pictures. There’s a conspiracy theory for you!

2 commentaires:

The "Hollywood" series was absolutely spectacular. I viewed about 4 episodes when they aired on my local PBS channel here in California back in '90. A shame that it's not available on DVD...

I completely agree. Hollywood is certainly among the greatest documentaries ever made on cinema. I hope one day it will make it onto DVD.

Enregistrer un commentaire